Table Talk: How to Live

Introducing a new column for Lean Out's paid subscribers - a kitchen wisdom-inspired newsletter on food, family, books, and the art of navigating modern life

For some time now, I have been grappling with the question of how to live. I love my work, am fortunate to have close relationships, and am generally pretty happy, but I feel a constant uneasiness about the state of our society.

It turns out I am ill-equipped for modern life. I find the pace dizzying and I can’t seem to catch my breath. The tsunami of information overwhelms me. The news headlines are awful but the view out on the streets is no less concerning. I spend too much time at my desk and too little time in the woods. The pods for my morning cup of coffee taste thin and synthetic, and after eating lukewarm, soggy takeout for dinner, I feel both overly full and deeply malnourished. I fret about microplastics in our food supply but am at a loss on how to avoid them. I struggle, always, with how disorienting and dysfunctional daily life has become — the unending petty hassles, from a subway machine that overcharges with no recourse to the Christmas cards that take a comically long time to be delivered in the mail. Everything is automated and divorced from our living, breathing existence; no human being ever seems to be at the end of the line. A feeling of unreality pervades all. The tangible appears out of reach.

This problem — which, at heart, is a problem of how to live — is not theoretical. It is practical. And I have decided it requires a practical solution.

Over the holidays, I read Paul Kingsnorth’s magnum opus, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity, which captures the unsettled relationship that I have to our increasingly digitized world. (Which, of course, both Kingsnorth and I make our living in.) The British writer, “recovering Environmentalist”, and convert to Orthodox Christianity offers a diagnosis that is at turns dystopian and profoundly poetic. But what’s stayed with me most is his prescription. To resist the inhumanity of the algorithmic world, he argues, we must reclaim the past, people, place, and prayer.

For me, there is no better place to do this than the kitchen. Being in the kitchen means being somewhere, as opposed to the anywhere that I inhabit at my desk, lost in the ether of the Internet. And at the end of the day, when I peruse neighbourhood markets for ingredients, the small stretch of city blocks that I actually inhabit comes into focus. Cooking is about the here and now.

Unlike so many contemporary pastimes, cooking is no solo endeavour. One cooks for others. I was reminded of this by my friend Leaughan, who is as good a cook as any I know. When she became my next-door-neighbour, after moving to Toronto from New Orleans, she began knocking on my door with plates of food. She’d made too many biscuits, she would tell me, or else too much soup or too big a batch of jam. We started sitting and talking over food, and then she joined my family for holidays, and then she became family. Now that she’s back living in the States, I cannot eat roasted potatoes without remembering her homemade onion salt, or sit down for a cup of chamomile flower tea without wishing I was in her kitchen drinking it. She taught me that cooking is about other people as much as it is about what appears on our plates.

Home cooking puts us in touch with the past, too, because recipes are essentially old family stories. When you are in the kitchen, stirring soups or whisking salad dressings, you are never truly alone but are instead accompanied by memories, and by the spirits of those who came before you. I cannot make onion soup from The Cooking of Provincial France without calling my mother and I cannot bake an English butter cake without missing my Nan. As my life has expanded, the kitchen has become crowded with more psychic visitors, leaning over my shoulder cheerfully offering tips. At Christmas, we made an Irish ham like the one my sister-in-law grew up eating in Dublin. (Or rather, we tried to.) And every Thanksgiving, my husband makes the Louisiana cornbread dressing that his father made before him, and that his grandmother made before that. Cooking is nothing if not a portal to the past.

As you might imagine, the prayer piece of Kingsnorth’s formula is sometimes harder for me to access. Raised as I was in the West Coast bohemian milieu, I’ve had little exposure to religion, unless you count the Buddhism of the Beat poets. I do crave myth and mystery, though, and I do hunger for the sacred, the transcendent. These past few years, to my surprise, I have found that nothing settles me more than a Catholic mass. The kitchen, meanwhile, gives me a space to mull over its meaning. Rolling out a pie crust is a good way to meditate on the values I aspire to, and to ponder how to make them real in my life. What does love and service really mean? What does it look like? I am trying to move away from the individualistic ethos of our time, and toward something deeper and more ancient and more sustaining. Cooking is a concrete way to put this into practice.

Here’s the thing: You don’t bake a Quebec Tourtière unless you intend to feed it to someone, unless you wish to celebrate and care for and nourish them. You don’t do it unless you believe, on some level, that we are our brother’s keepers. In rolling out that dough, and sautéing and seasoning that meat, you glimpse this greater reality. You sense that we are all connected, and that to behave otherwise is folly.

I should add that there is also, for me, the act of writing it all down afterwards. The author who has most influenced my life, Madeleine L’Engle, believed that writing itself was a form of prayer. As I write to you now, I can feel that familiar sense of calm. I can feel a delight in the ordinary returning, along with a desire to rejoice in the goodness of the world, broken as it is.

This brings me to the matter, reader, of what this all might look like on the page. Is this a food column? Is it a personal essay? Is it supposed to be about books or politics or life? None of the above? All of it? Thankfully, in this, our New Year’s Day podcast guest Valerie Stivers points a path forward. Her book, The Writer’s Table, is based on her long-running column at The Paris Review, and is itself a mix of genres, combining food writing with literary criticism. My conversation with Valerie gave me permission to experiment, and put me back in touch with a part of myself, and our culture, that I hadn’t been able to access for some time. Both Valerie and I spent time in the magazine world, and we both took up cooking while writing and editing food pieces. (This, we share with Joan Didion, who learned to cook proofreading recipes at Vogue in the 1950s.) In her book, Stivers profiles a number of famous writers who adored food, including the late Laurie Colwin.

Colwin is the model for what I would like to do here in the coming weeks and months.

Have you ever read Laurie Colwin’s Home Cooking? If you haven’t, I suggest you go directly to your local library and check a copy out. I did so, over the holidays, and devoured it in a day. It had been years since I read it, and it took me back to a different era. Though it is ostensibly a collection of her columns from Gourmet magazine, it sits comfortably in the genre of food memoir, along with Nora Ephron’s autobiographical novel Heartburn, Molly Wizenberg’s collection of stories and recipes, A Homemade Life, and Ruth Reichl’s coming-of-age tale Tender at the Bone. These books are warm and intimate. They are often quite funny. They know how to make a story sing. Ultimately, they invite you to relish the small, delicious details of your life. A pan of hot shepherd’s pie, served to loved ones on a windy night. A plate of chocolate chip cookies, eaten with your feet up after a long day. Strong black coffee at dawn, as you watch snow fall outside your front window. These moments are, in fact, an antidote to the darkness of modern life. They are a way to let the light in.

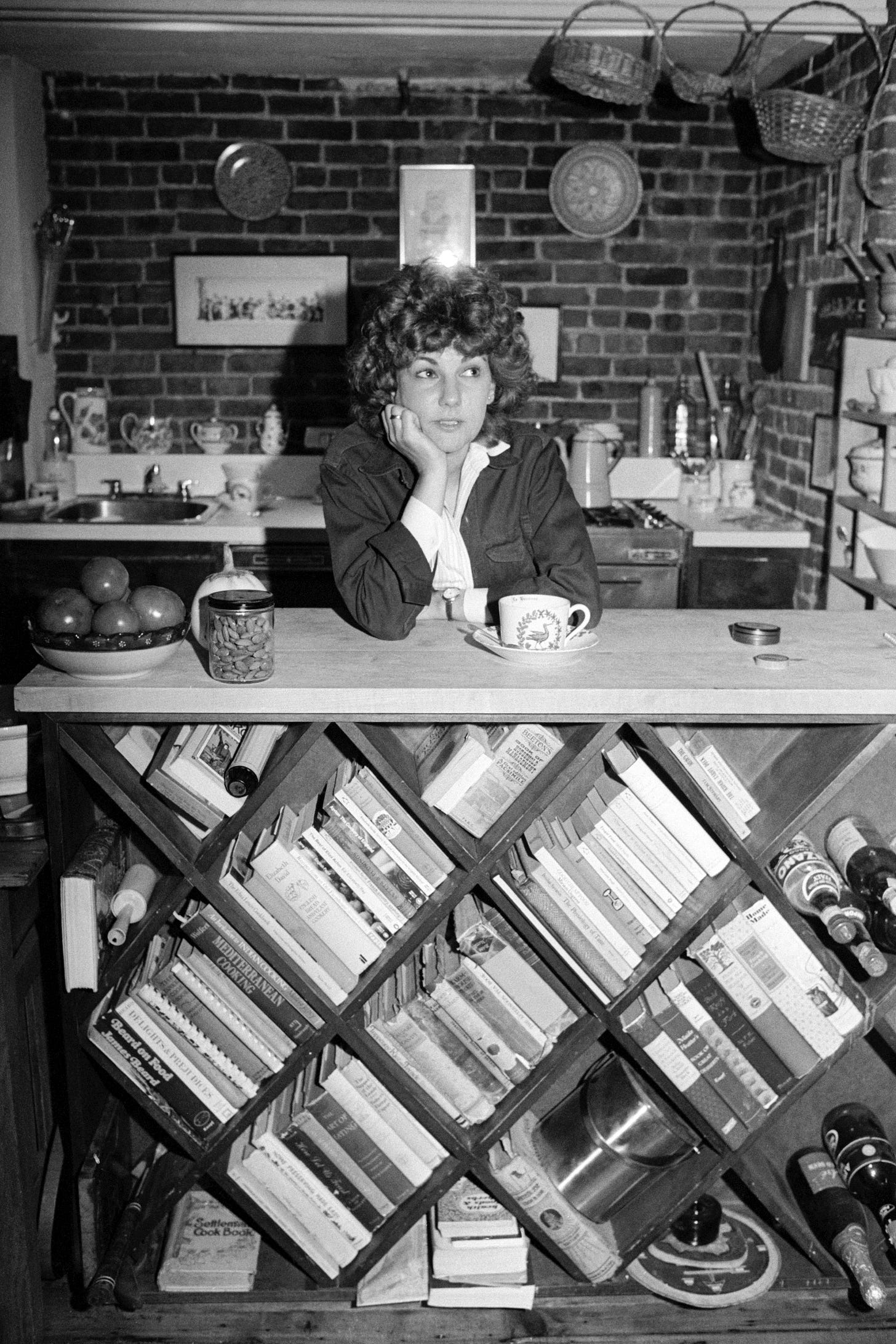

Colwin’s work evokes all of this and more. It is generous and unpretentious. She makes stewed eggplant on a hot plate in a tiny Greenwich Village studio apartment and washes dishes in the bathtub. Her guests eat on a folding card table. Kitchenware comes from flea markets. Even her instructions are irreverent: “Drain the orzo and throw in a lump of butter. Stir it in, add the broccoli, some fresh black pepper and some grated parmesan, and you have a side dish fit for a visiting dignitary from a country whose politics you admire.” She consults cookbooks from the 1920s and waxes poetic about British cuisine (making me hungry for ginger cake). She relays cooking catastrophes. She admits to serving baked chicken so many times — she jokes she could make it under general aesthetic — that her friends complain. In short, Colwin invites you into her life. Her food columns, as The New York Times once put it, are “like phone calls from a dear friend.”

I once did a fair bit of this kind of writing and I have to say that I miss it terribly. A Lean Out subscriber, Aleksandra, recently read my first book and paid me the enormous compliment of comparing it to “a long letter a close friend would have written to me.” This year, this kind of writing is what I aspire to. This is what I want to reclaim, to recapture.

This new Table Talk column will sometimes include recipes, which you are welcome to try and offer feedback on. But be forewarned, I am no fancy cook. I like simple, accessible, quick food. I care about thrift and I care about comfort. What I crave, above all else, is home food. To my mind, there is no better gift for nieces and nephews or neighbours or new parents than plain banana bread, whipped up from a handful of ingredients, warm from the oven. My food is not overly healthy — I do not swear off white flour, for instance — but it is certainly better for you than processed food, and it generally doesn’t taste like cardboard either. I also firmly believe that when it comes to wellness, pleasure should count for something.

This column will be behind a paywall going forward, reserved for Lean Out’s paying subscribers. Many of you have been here for years now, and I want to give you something extra in 2026. Think of it this way, if you will: The podcast, which is always free, will be your meat. The transcript will be your potatoes. Table Talk will be a dessert of sorts. Hopefully it will be something a little more friendly, and, dare we say, joyful. A chatty letter from a friend, to be consumed over coffee as we navigate the troubled waters of modern life — refusing to relinquish our humanity and our freshly baked banana bread.

People frequently ask me how to survive the insanity of the news. This is the best answer I’ve come up with so far.

Easiest banana bread ever

Adapted from the 1980 cookbook, Mama Never Cooked Like This, from Susan Mendleson, founder of The Lazy Gourmet in Vancouver, Canada

1 and 1/4 cups of flour

1 teaspoon of baking soda

2 ripe bananas

2 eggs

1 stick of butter (salted or unsalted), melted and cooled - it should be 1/2 cup of liquid

1 cup of brown sugar

Grease a loaf pan well and preheat the oven to 350F. Sift flour and baking soda into a bowl. In a separate bowl, mash the bananas and stir in the brown sugar, eggs, and cooled melted butter. Stir the wet into the dry until you no longer see streaks of flour. Pour into the loaf pan and bake for about 1 hour, starting to check it after 50 minutes. (Watch closely, it can burn easily.) When the crust is browned and a toothpick comes out clean, it is done. Use two knives to free up the sides of the loaf and then carefully transfer it to a cooling rack. After 15 minutes or so, it’s ready to slice, slather in butter, and share with someone you’d like to befriend.

I love love love this Tara! Yes cooking was a way to nourish those we love and somewhere, like most things, it got lost along the way and replaced by fanciful experts extolling the virtues of organic butter. Ugh.

I scribbled down your recipe for pancakes on the inside of my kitchen cupboard door above the kettle, that you had provided on your first Mother’s Day column. My kids love it and I use that recipe every week. Nourishing and delicious food IS fancy, and is a calling to sit, enjoy, and eat! I look forward to your latest endeavour.

"Turns out I'm ill-equipped for modern life"--this is how I feel. Also, speaking of disconnects, it took me four attempts signing in and out to make this comment. But I persevered. :-) Looking forward to your column and also to reading Kingsnorth this year!