Over the last few years, many of us have had the feeling that things were just not adding up, that the narratives in the mainstream media simply were not making sense. Well, my guest on the podcast today had that experience earlier than most, years back, with online feminism. And it sowed the seed that became her most recent book.

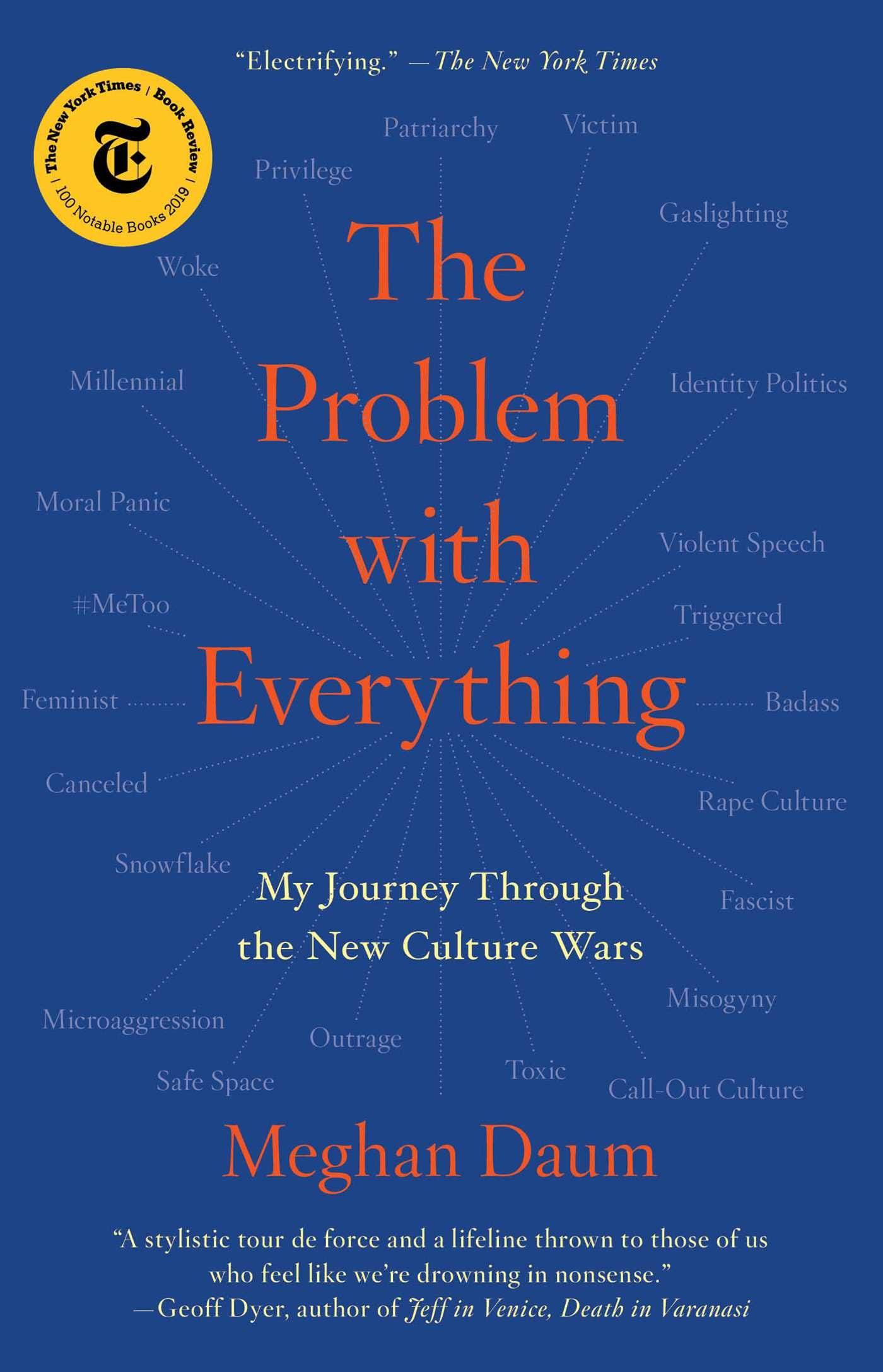

Meghan Daum is an essayist and the author of six books. She’s a former opinion columnist with The Los Angeles Times and the host of a weekly interview podcast, The Unspeakable. Her latest book, The Problem with Everything: My Journey Through the New Culture Wars, was recently released in paperback in Canada with a new introduction. Meghan joins me today to talk about the excesses of #MeToo, about cancel culture, about Elon Musk — and about the rise of heterodox thought.

TH: Meghan, welcome to Lean Out.

MD: Thanks for having me. It’s great to be here.

TH: So nice to have you on. I first read The Problem with Everything in the summer of 2020. I was working on a current affairs radio show, and it seemed like every topic that I was interested in was off limits. So, it was a relief to read your book. And it was a gateway drug to other heterodox thought. I know you have a new introduction to the book. With some distance — with the last two years of heated culture wars, plus a pandemic — what’s it like for you looking back on the book?

MD: First of all, thank you for reading it and I’m really glad it resonated with you. The book was excruciating to write. I’ve published six books and I have never had a challenge like this before. I started writing it in 2016 and it had many iterations along the way. But to answer your question, how do I feel about it two years out? I guess I feel like I thought things would have changed, and I’m unpleasantly surprised that they seem to have gotten worse.

I feel like the book captures the moment that it landed and everything leading up to it. It’s impossible to hit a moving target. There’s a reason that when people are covering the current culture, they tend to do it best in columns, in weekly installments. It’s very hard to capture these kinds of cultural phenomena in a book. So it remains very much of its time, but it has certainly continued to be relevant. In fact, more so. People are responding to it better now than when it first came out.

TH: That’s interesting. As you say, it is of its time, but it really captures a lot of the forces that led up to this Great Awokening that we have been living through. I want to talk about #MeToo; you write about that extensively. Take me back to when the Aziz Ansari story came out and what you were thinking and feeling.

MD: I think I was thinking and feeling what most women were. It was really the record scratch moment. I think that might have been Bari Weiss’s phrase. People were more or less going along with the #MeToo movement; obviously there was much good that came out of it. But like so many of these movements, the overcorrection comes with a lot of unintended consequences. So, you have situations like Aziz Ansari. That was not a #MeToo situation as #MeToo had come to be defined. That was a misunderstanding … I think that a lot of people who had been going along with #MeToo in good faith took that situation as an occasion to take a step back and say, “What are we doing here? What are we critiquing? What kind of behaviour do we really mean to be calling out? Let’s slow down.” But I’m not sure we did slow down. Alas.

TH: Yeah. When you were writing about the ironic contempt for men leading up to that moment, the #KillAllMen, the “I drink male tears” boasts on social media, that soon became inseparable from actual disdain for men. I worry sometimes listening to younger women talk about men now; I hear that disdain there. Do you think there was enough internal criticism from feminists, as this was all bubbling up?

MD: Well, criticism is anti-feminist. Self-criticism is the opposite of self-care, and self-care is now synonymous with feminism, right? I mean, my book is a self-interrogation, if nothing else. I’m self-scrutinizing the whole way through. That’s just what I do in life, and that’s what I’ve always done in my work.

I think that it becomes very difficult to examine anything in any depth — yourself, the world, other people — when you are dealing with everything being on screens, and every kind of media experience being incredibly short. This goes for all of us. If you’re in these younger generations, that’s just the air you’ve been breathing since you were born. But even those of us who are older, we still fall victim to this. We are all headed down this very dangerous path with respect to our abilities to look at ourselves with any degree of honesty, and also look at the world and get past our own confirmation biases. And understand the difference between how things are and how we want them to be. Because those two things are often very much at odds.

TH: In the book, you list some media headlines, and there’s one that really stood out, a BBC headline in 2018: “Climate change impacts women more than men.” This trend is very much present with us now. We’re used to it — this rolling emergency, and everything being about this one thing. But I don’t remember that happening before #MeToo. I wonder if this contributed to the backlash that we’re seeing now. I remember Dave Chappelle warning about this in one of his specials. What do you think about the backlash that we’re seeing?

MD: Well, there’s always been that kind of hyperbole in media. I mean, that was always a joke in news organizations. There would be a headline: “World ends, women and children affected the most.” So, there’s always been that kind of tendency. But, yeah. The reason that I was moved to write about this stuff was because I grew up in the 70s and the 80s, and I was a young woman in the 90s. And the feeling — it wasn't just a feeling, it was a fact — was that women were doing better than men, on balance. Women were graduating from college and getting higher degrees in greater numbers than men. They were buying their own homes as single women, much more so than single men.

Across any number of metrics, women were surpassing men. At the same time, there was this narrative on social media, and in the digital media sphere, in a lot of online journalism, that really took as its premise that women were suffering. That women were a marginalized group. That it had never been a more sexist time. That even to walk down the street and fight the patriarchy at every corner, meant that you were a badass that needed to be congratulated. It didn’t make any sense to me. I wrote the book as a way of trying to figure out what I was missing.

TH: You write about toughness. I loved reading that, and it made me think. I started my career in hip-hop and I experienced sexism. But the way I thought about it was: This toughened me up. I felt good about myself, that I could be tough in those ways. But that’s not how the next generation of women sees it. Is there a middle ground between us probably putting up with more than we needed to, at times, and them embracing their vulnerability?

MD: I think that our generation, we probably overvalued toughness. We fetishized it. And millennials, Gen Z, they perhaps overvalue or fetishize fairness. And we really need to meet in the middle. I remember there was a critique of the book that said: “Why is she taking all this time to praise toughness and talk about how important it is to be tough, instead of working to build a world where toughness is not necessary?” I mean, that’s absurd. We call this the naturalistic fallacy. Just because something is true doesn’t mean that we like it. You’ve talked about this a lot in your work, with biological clocks, and the biological imperative, and the differences between the sexes. In fact, there are things that women can’t do that men can, and vice versa. It’s never going be fair. It might be equal at the end of the day, but fairness is a very different thing.

TH: I worry about some of the trade-offs, as well. I worry about the hostility between the sexes, the sex recession, the real trouble young people are having dating and connecting. It just seems like we’ve lost some pretty big things along the way. And yet talking about that is still difficult.

MD: It’s funny, though, is it difficult? Because we’re not allowed to talk about the biological sex, and all that. But I feel like there’s a world in which it’s difficult, or where we’ve decided that it’s difficult — and that’s the Twittersphere, and these very small echo chambers of discourse. Academics and activists, and, you know, writers for Buzzfeed or whatever. But that’s a very tiny percentage of the world and the culture.

In the real world, people can talk about this stuff all the time. And they actually do. I’m at a place now where I think, as a journalist, or as a public thinker, it’s really your job to get past what your colleagues or your peers expect from you — or some kind of arbitrary standard that they’ve set for acceptable conversation — and just talk like a normal person.

Because I guarantee you, if you go out to a restaurant on a Friday night and there’s group of young women sitting around at a table, drinking wine and talking about their lives, they are going to be talking about the differences between men and women. They are going to be talking about their frustrations in so far as they relate to real biological realities. Unless you happen to be in the Social Justice Warrior Tavern, on balance, normal people are still talking about normal stuff. And I think that we, as media people, need to be mindful of that.

TH: You wrote in the book about the discovery of “free speech YouTube.” I remember you talking about this when you had John McWhorter on your podcast, which was just such a strong interview — going through losing your marriage and finding this new group of intellectuals. For our listeners, walk me through what that transition was like for you.

MD: Yeah, I wrote about this in this piece called “Nuance, A Love Story,” which appeared on Medium. It was this very long, very viral in the end, piece. So, yeah, I was married. I got married relatively late in life. We were in our late thirties. The marriage had problems, but we were very much intellectually aligned. We were always on the same page when we talked about ideas in the world. So, when I lost the marriage, I lost my intellectual ally. This was around 2015. A lot of my friends and colleagues were drifting over into this other space — the one we were talking about earlier. The ironic misandry, and rolling their eyes at men, and taking cheap shots at men and the patriarchy. People that I thought were relatively sophisticated were suddenly acting very adolescent and juvenile in their thinking. I think it was a way of signalling to each other that they were on the right side, and also gaining audience by doing that.

That was a very alienating experience. I started to feel kind of lonely. And I stumbled on John McWhorter and Glenn Loury having conversations on something called bloggingheads.tv, which had been around for a long time. They would call themselves the Black guys on Blogging Heads. They talked about race in this extraordinarily nuanced, honest, unapologetic way. It was exhilarating. And then, of course, the YouTube algorithm led me down the path and I started discovering other thinkers. I realized that there was this world of people having really great conversations on YouTube. These conversations were just not available in mainstream media anymore. Certainly not on NPR; not on any interview show. It was remarkable. And so that was the beginning. I didn’t really step away from the mainstream media, I was sort of pushed out. But coincidentally, the structures were falling apart anyway. So, good riddance.

TH: When I was reading about that, I was thinking how many people probably would relate to that, going through that experience in the pandemic. That extreme isolation on the one hand, and then the conformity of thought just pushing down on you. I remember reading an essay from William Deresiewicz, saying your podcast did that for him.

MD: Oh, that’s so nice to hear.

TH: He said in his essay that he was listening to your podcast, and it was filling that void for the conversations that he was not getting other places, like NPR. What do you think that experience is that we all went through? When we’re in such isolation, and we’re in this cultural crisis, and there’s this lifeline of these big conversations that you can’t have elsewhere.

MD: I think it’s just feeling like you’re not crazy. Because, you know, you watch the news, you watch CNN or listen to NPR, read The New York Times, and you’re being fed this narrative. It isn’t completely wrong. But there’s always just something off. The framing is such that you start to smell something kind of bogus. And then it makes you feel very alone when you see your friends and your family members and your colleagues buying into it, without thinking, often. I think those of us who were kind of sensitive to that bullshit — let’s just call it what it is — ended up finding each other.

I always want to be clear about this: It’s not like we all have the same views. This word heterodox has arisen; it’s not a great word but we can’t seem to find a better one. People say, “Well, what does that mean?” To me, it just means that you form your opinions on an issue-by-issue basis, rather than lining them up according to one side. Some people think heterodox means alt-right-adjacent, or something like that — which could not be farther from the truth. You get people with all kinds of views under this heterodox umbrella. I like to just think of it as people who are allergic to bullshit. It’s that simple.

TH: It’s a good way of putting it. I’m glad you brought up that alt-right thing, because the knee-jerk reaction to anyone on the left criticizing the left is to call us right-wing. I want to read a passage from your book: “I would have taken equal if not more delight in criticizing the political right if there was anything remotely interesting or surprising about doing so. But bashing the right, especially in the age of Trumpism, was easy and boring. Inspecting your own house for hypocrisy was a far meatier assignment.” You had this conversation with Jon Kay recently: What is a conservative? Why do you think all the dissenters from the left now are being painted with this brush — what is this about?

MD: Well, during the Trump administration, the idea was that we couldn’t afford to inspect our own house. We can’t afford nuance, because a nuanced discussion can easily be weaponized by the other side. The thing is, you can really only be canceled by your own side. If you’re on the left and you get criticized by the right, that’s actually good, that helps you. That gives you currency. But to be cast out by your own side becomes a real problem.

This actually started well before the rise of Trump. I was noticing this in 2014. People started saying, “I’m going to call you out.” The call-out culture, I was seeing that in 2013. But certainly, by the time we got to Trump, there was a feeling among Democrats that we were in an unprecedented crisis and that anybody who was not going to join the resistance, in exactly this way, was helping the other side — might as well be helping Trump. That we could not afford any kind of complexity in any of our discussions. And I think that remains, that sense of catastrophe. Now we see it around Covid.

TH: You asked Jon Kay, as well, about what he tells younger writers. I know in your new introduction to the book you return to that question. Your old answer was: Be brave. Your new answer in the intro was: I don’t know. What’s your answer today?

MD: I really don’t know. The thing is, I don’t know is the only honest answer to anything. A lot of these podcasts, and these nuanced conversations we’re all trying to have — the ones that really get big audiences and get the most attention are the ones where the guests or the host is willing to say, “Well, I do know, here’s the answer. This is what’s happening, full stop.” And that’s never true. The only truly honest answer to anything is we just don’t know … In terms of what to tell writers, it’s really hard. I’m teaching an online personal essay memoir workshop right now. Just before we started, I went on Facebook and said to everybody, “Can you guys name some publications where my students might be able to submit their work? Because I honestly can’t think of any place anymore.” I’ll be curious to see what people say.

TH: To close, I wanted to read a passage from your book that really stood out to me: “We need to stop devouring our own and canceling ourselves. We need fewer sensitivity readers and more empathy as a matter of course. We need to recognize that to deny people their complications and contradictions is to deny them their humanity.” I loved that. Are we any closer to this point that you are advocating for?

MD: No, I don’t think we are. I think that there is a growing movement of people pushing against it. But the reason that the movement is growing is because the problem has grown … Until we get to a place where the adults can actually act like adults, we’re going to be stuck here. I often say that if the smart, thoughtful people don’t speak out, the stupid thoughtless people are going to continue to do the job. But often the smart people are smart enough to know when to keep their mouths shut … We really just need to see institutional leaders, people who can afford to take some hits, actually standing up and taking them. Because I think when people start to do that, others will follow.

This transcript has been edited and condensed. For the full interview, download the podcast.