Weekend reads: A remembrance of things past

Maureen Dowd, Nora Ephron and Lance Morrow on the magic of newsrooms

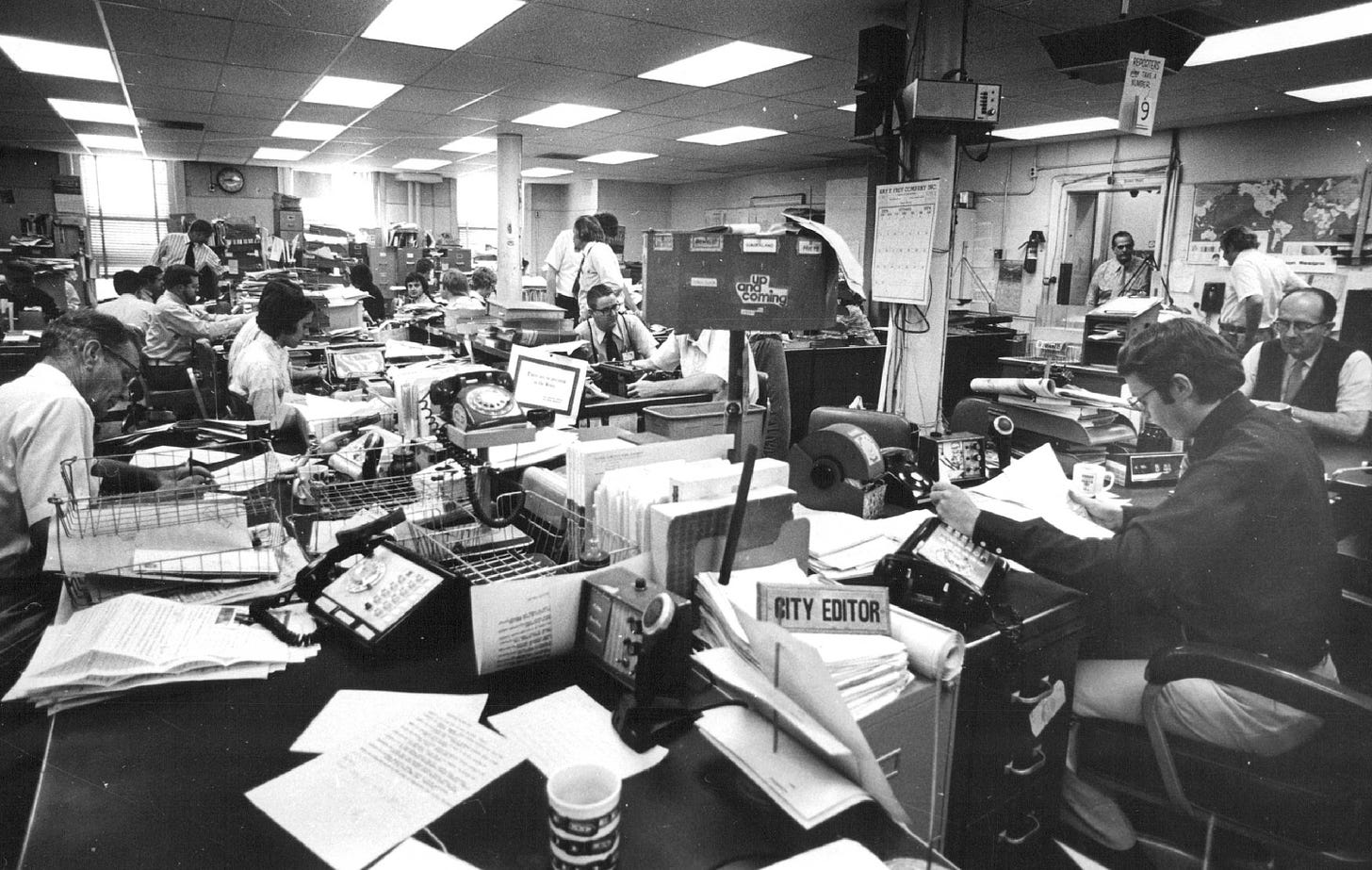

This past week, Maureen Dowd at The New York Times penned a moving elegy for in-person journalism, “Requiem for the Newsroom.” In the current era of remote work, she argues in the piece, media culture has lost its collegiality, its spontaneity, its charged energy. In other words: Its magic.

“There was an incredible camaraderie and panache about the whole endeavor, whether we were pursuing stories about murder, politics or the breeding woes of the pandas at the National Zoo,” Dowd opines. “Conversation and competition,” fellow journalist David Israel tells her, turned newsrooms “into incubators of great ideas.”

There’s a reason — another journalist, Mark Leibovich, tells Dowd — that movies were made about newsrooms, from All the President’s Men to Spotlight. “Newsrooms were a crackling gaggle of gossip, jokes, anxiety and oddball hilarious characters,” the reporter Mike Isikoff muses to Dowd. “Now we sit at home alone staring at our computers. What a drag.”

Dowd’s grief for this lost newsroom era is palpable:

The legendary percussive soundtrack of a paper’s newsroom in the 1940s was best described by the Times culture czar Arthur Gelb in his memoir, “City Room”: “There was an overwhelming sense of purpose, fire and life: the clacking rhythm of typewriters, the throbbing of great machines in the composing room on the floor above, reporters shouting for copy boys to pick up their stories.” There was also the pungent aroma of vice: a carpet of cigarette butts, clerks who were part-time bookies, dice games, brass spittoons and a glamorous movie-star mistress wandering about …

Forty years later, when I began working in the Times newsroom, it was still electric and full of eccentric characters.

She laments the next generation, who have no idea what they’re missing:

I’m mystified when I hear that so many of our 20-something news assistants prefer to work from home. At that age, I would have had a hard time finding mentors or friends or boyfriends if I hadn’t been in the newsroom, and I never could have latched onto so many breaking stories if I hadn’t raised my hand and said, “I’ll go.”

As it happens, Dowd is right to mourn the loss of the newsroom.

There was a romance to newsrooms. They were adrenaline-fueled, chaotic, exciting places. They were home to gallows humour, late nights and early mornings, and a cast of witty cynics who often revealed themselves to have big hearts. Plus: Breaking news, astonishing phone calls, impossibly tight deadlines. Insurmountable obstacles that were, in one way or another, surmounted.

Utterly spent at the end of a long day, you often felt as if you’d run a marathon.

There was always, too, the feeling of being at the very centre of our culture. Of watching history unfold in real time. Of standing in the midst of a relentless storm, and somehow managing to keep your bearings. But only just.

My memories of news events — when Toronto’s mayor was discovered to have smoked crack, say, or when a flight carrying Canadians was shot down in Tehran — are all tied up in memories of the newsrooms that I was working in at the time. The desks I sat at while I made call after call, the TVs I huddled around with colleagues to watch coverage, the bitter coffee we drank to steady ourselves.

My first newsroom was at a student paper at my university in Burnaby, B.C., where I sought solace in the days after the planes crashed into the twin towers. My last newsroom was at CBC Toronto, where, during the pandemic, I went into the studio for a time to direct our local morning show. My memories of the pandemic are inseparable from the desolation of that newsroom, the emptiness of the studio. The starkness and silence of a building that was once full of life.

And then, the many months before and after that, all of us at home, online, producing current affairs radio during the crisis of a lifetime. My colleagues and I scattered across the city, our shared coffees now reduced to flashes of mugs on a screen.

The isolation made me immediately, inconsolably nostalgic for all that we had once had. All that we had taken for granted. The newsroom, the noise, each other.

One of my favourite essays of all time, Nora Ephron’s “Journalism: A Love Story,” is about a then-already vanishing newsroom culture.

In the piece, Ephron recounts her early days at Newsweek. “It was exciting in its own self-absorbed way, which is very much the essence of journalism: You come to believe that you are living at the center of the universe and that the world out there is on tenterhooks waiting for the next copy of whatever publication you work at.”

If Ephron pokes fun at journalist’s self-importance, though, she is reverent about the job itself, and all it involves — including the roller coaster that is the newsroom.

Here she is on The New York Post, where she landed after Newsweek:

In those days, the Post published six editions a day, starting at 11 a.m. and ending with the 4:30 stock market final. When news broke, reporters in the street would phone in the details from pay phones and rewrite men would write the stories. The city room was right next to the press room, and the noise — of reporters typing, pressmen linotyping, wire machines clacking, and presses rolling — was a journalistic fantasy.

Newsrooms were where you learned the craft, often by piecing things together for yourself, generally at breakneck speed. Some of the best journalism advice you’ll ever read is buried in a paragraph in this Ephron essay. I know I needed to read it:

She also told me that when I got an assignment, never to say, “I don’t understand” or “Where exactly is it?” or “How do I get in touch with them?” Go back to your desk, she said, and figure it out. Pull the clips. Look in the telephone book. Call your friends. Do anything but ask the editor what to do or how to get there.

That old ethos of gumption and self-reliance and mental toughness was a huge part of what we absorbed in newsrooms. It was as ambient as the ever-present noise.

And how noisy it was.

In my day, the typewriters were gone, of course, but the phones remained, and you picked up so much by listening. You learned everything you needed to know by eavesdropping on the phone calls happening all around you. You heard how to stand up to pushy public relations reps, or “flaks.” How to be polite but firm with interviewees who sought to control an interview. How to gently encourage reluctant subjects to go on the record. How to call around and check facts, how to demand specificity, how to phrase questions so as to extract as much information as possible. How to express quiet empathy when subjects shared painful things.

You learned, too, how to work to the clock, how to throw your hat in the ring for assignments, how to fight for a story, or a guest, or a point of view.

Perhaps best of all, you learned how to let all that tension subside. How to walk outside of the building with a colleague, to inhale the crisp morning or night air, to buy steaming paper cups of coffee, and to talk of other things.

Is there any more useful skill than that?

All of this made me think of a recent book, The Noise of Typewriters: Remembering Journalism, which captures a similar spirit.

For 40 years, during the height of magazine journalism’s influence, “the age of magazines,” Lance Morrow was an essayist at Time. His memoir serves as an extended — and hauntingly beautiful — meditation on the decades of print media’s prominence, and all that he saw and did during that period.

Morrow — the son of two Washington, D.C. journalists who passed on “the idea that history is a small town” — recounts tales of Time’s legendary founder Henry Luce, and touches on the early days of his own friendship with Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein, at The Evening Star, a “sweet, slightly antiquated newspaper” with a first-rate staff and “old journalistic virtues,” including editors who were “puritanical in their devotion to facts.” (“Carl was a serious student of newspaper work and how it is done,” Morrow notes. “I was not. Carl had immense respect for the work — a sort of awe — and I had little. I was a snob and a little ashamed of the triviality of the stories we had to cover.”) Morrow mulls over Ernest Hemingway’s prose, as well, and shares amusing anecdotes about Joan Didion and Nora Ephron, along with other luminaries.

In the process, he presents a highly nuanced portrait of the press, in both its triumphs and its dismal failures. Consider this passage, from the book’s opening, which sets the tone for all that is to come:

Is journalism inevitably engaged in the working up of myths, whatever its pretensions to objectivity? A journalist needs a disciplined reverence for the facts, because the temptations of storytelling are strong and seductive.

I don’t mean that mythmaking is necessarily perfidious: in any case, it is inevitable. It’s a problem of storytelling and, so to speak, of entertainment. Where journalism in concerned, as I discovered over the years, the narrative line is not only a chronic problem of ethics but the key to culture itself — and even the glue that holds a society together.

But in the era I am writing about, questions like that were above our pay grade. We took it for granted that there was something called the truth and that it could be discovered …

In the twenty-first century, on the other hand, journalism would find itself plunged into the metaverse. Politics and culture would migrate into the country of myth, with its hallucinations and hysterias — the floating world of a trillion screens. There might come to be no agreed reality at all.

The Noise of Typewriters seeks, in its rambling, whimsical way, to address an important, and enduring, question: Why do we journalists continue to do what we do? “Most journalism evaporates in a day or a week,” Morrow writes. “Why bother about it, then, such a shabby, evanescent thing?”

The answer, not surprisingly, is found in the newsroom.

Take this snapshot, in 1965, of an evening in the Time-Life Building in New York:

One Saturday night that summer, we made last-minute changes on the “yellows” (the final edit before a story went to the printers) and wrote captions and waited for “checkpoints” to clatter into the wire room from correspondents in the bureaus. Everything was done on paper: computers lay far in the future. Researchers, all women, hurried in and out of the room with fixes — “red changes” — on the copy. We were gathered in Gus’s office and drank Johnny Walker Red or Bombay gin (the Luce operation was famous for its good liquor.)

On this particular Saturday night, we watched the Watts riots on Gus’s color television set. Watts was the first of the great summer riots of the 1960s. We watched mostly in silence, except for the rattle of the ice in our glasses. We’d had three or four hours’ sleep the night before — the usual routine toward the end of the editorial week. The Tower Suite sent down a catered roast beef dinner, and we went off to eat at our desks. Accounts of the old days at Time always made much of our liquor carts and the catered dinners and the fancy expense accounts, and all of that was true. But the work was hard and the standards, on the whole, were exacting and obsessive; the editors, sometimes spectacularly neurotic (one of them ate pieces of paper when he was agitated), were also intelligent and sometimes learned; the people one worked with were, many of them, splendid and gifted and eccentric. Time Inc. was interesting and demanding universe.

The answer to why we journalists persevere, then, is in the details. In the simple tasks we perform over and over, under stress and strain, but with a growing reverence, and, hopefully, a growing mastery. As Morrow illustrates:

I wrote in my notebook: “Never be certain that there is no meaning. Never be certain about anything too quickly.”

All journalism implies a concealed metaphysics — even a theology: All truth is part of the whole. All is in motion.

Be tolerant of chaos. Be patient. Wait for stillness.

That is Journalism 101, according to me.

Other lessons relayed here, from Morrow and peers he admires? “Luck emerges from diligence”; in interviews, silence is a powerful tool; good journalism is “endlessly time-consuming,” requiring “supernatural patience, determination, perseverance”; and “real America [is] not in Washington or New York but [is] to be found out there, out in the country.”

History, Morrow muses, “both as it is lived and as it is written down, may be understood as an immense weave of storylines and perspectives that have their own hierarchy, different angles of approach. A great mingling of realities.”

Or, as Philip Graham, publisher of The Washington Post and Newsweek, once put it: “Let us today drudge on about our inescapably impossible task of providing every week a first rough draft of a history that will never be completed about a world we can never fully understand.”

The journalist’s primary job is, as Morrow sees is, to show up. “Being there is one of the imperatives of journalism,” he writes. “Or it used to be, before the age of screens, which changed everything. Being there is still a good idea.”

Our task, then, is to bear witness. It is the larger purpose that animates all we do.

Articulating journalism thus, as a kind of “sacred work,” Morrow employs lyrical, and even spiritual, prose:

Theologians refer to the creatio continua: If it is true that we live, moment to moment, in the ongoing Creation — in the rich and suspenseful unfolding of the All, of all the realities and all the illusions, of the mind of the universe or whatever it is that we call God — then the journalist has the important work to do: as witness, as Ishmael, charged to report and to understand and, as necessary, to warn the world. The journalist’s job is to keep watch over the ongoing Creation. Who else will do it? Politicians? Lawyers? The White House press secretary?

One could be forgiven for thinking this all sounds a bit high-minded for people who essentially just talk to others for a living. Undoubtedly, there’s merit to such a view.

I suppose the question is this: What kind of journalists would you prefer — ones who feel a deep pull to serve society, who possess an obsessive work ethic and an almost religious devotion to detail, but who likely take themselves too seriously? Or ones who don’t take themselves, or their work, seriously at all? Who send blasé, smug “lol” tweets all day long, lobbing cheap shots at anyone who happens to cross their paths? And, in what little actual work they do perform, mindlessly chase clicks?

Do we want cold, calculating careerists, forever striving for status among their in-group? Or do we want those who, in the words of Henry Luce, become journalists in an attempt to “come closest to the heart of the world”?

It’s no mystery what my answer would be.

I’ll leave you, reader, with some Lean Out updates: Podcast guest William Deresiewicz has a fantastic interview over at Persuasion; it’s one of the best articulations of the ethos of progressive elites that I have ever heard. Absolutely stunning.

Plus: Lean Out guest Hadley Freeman has a lovely, heartening Coronation piece on Queen Camilla in The Sunday Times, and Lean Out guest Nadine Strossen has made a compelling case for free speech in New Zealand. It’s well worth a watch.

Stay tuned, my guest on the podcast next week is legal scholar Erika Bachiochi, founder and director of the Wollstonecraft Project at the Abigail Adams Institute. She’ll be on the show to talk through a powerhouse panel that she recently moderated at Harvard, “Rethinking Feminism” (which features previous Lean Out guests Louise Perry, Christine Emba and Mary Harrington). See all you next week!

Thanks for posting the Persuasion link by William Deresiewicz, Tara. Not to compete with your great work, but I think every free thinker (critical thinker) should read this piece. He nailed it as to how the liberal elites got to where they are today. I read it yesterday, then printed off the transcript and read along while I played the audio. I wish I could articulate matters like that. ps - Thank you so much for being on Substack. There are a lot of folks (like me) who really appreciate what you think and say in the cause of current events and freedom.

I loved reading this piece. What great scenes are portrayed by the three writers.

From Nora Ephron: "That old ethos of gumption and self-reliance and mental toughness was a huge part of what we absorbed in newsrooms. It was as ambient as the ever-present noise."

What Ms. Ephron describes, was not just the province of the newsroom, but permeated much of working life in the past. Now, rather than being attracted to the energy and accomplishment that work can provide, the current fragility consumed zeitgeist fosters a demeaning focus on "work-life balance" and a host of other namby-pamby approaches to life.