Weekend reads: 'It should be satirized'

A Q&A on ideological extremism, identitarian infighting and CanLit conformism - with the Vancouver novelist Patrik Sampler

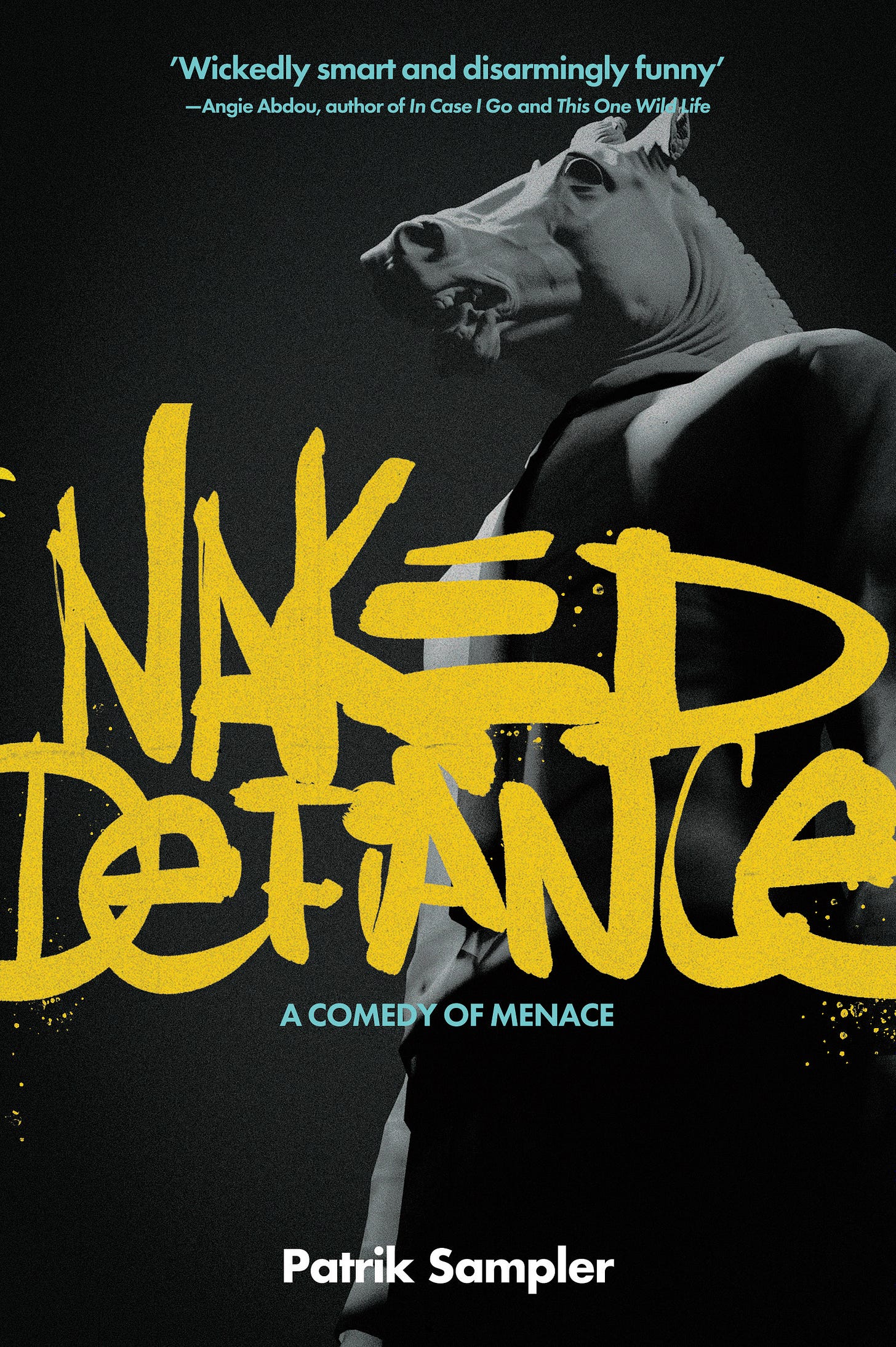

This week at Lean Out, we’ve been diving into the Canadian literary scene — and talking to writers that are pushing back on the status quo. Wednesday on the podcast, we spoke with the Toronto poet Michael Lista about his new collection of poems, Barfly. And today, we turn our attention to the Vancouver author Patrik Sampler, who’s penned a metafictional novel, Naked Defiance, that skewers the extremist politics of our age. Here, in this edited and condensed interview, Sampler contemplates identitarianism, social satire, and the state of CanLit.

TH: Your novel is about a pseudo-Marxist, anti-authoritarian performance art group that implodes … The group undertakes “actions” that are entirely symbolic, totally divorced from material conditions — and really from any political impact. Naked Defiance reflects currents in our contemporary culture, and satirizes them in nuanced and funny ways. Anyone coming from the progressive left, and dismayed with the turn it has taken, will find lots to recognize here. You were writing this novel at the height of the identitarian movement. In Vancouver, where I’m from and you live. As far as I can tell, Vancouver went all in on this. What did you see, during the years that you were writing this, as you were looking around at our culture?

PS: I saw identitarianism ramping up and ramping up. The question in my mind was always: When are we going to reach peak identity? I don’t know when it’s going to stop, but I think there’s starting to be some questioning of it now.

There’s always been a focus on identity in Canadian literature, but then it kept getting even more and more specific over time. Whereas it used to be, “I’m going to write a novel about my identity,” it became even more circumscribed — the parameters for identity kept shrinking and becoming more specific … There started to be some fear that if you questioned this trend, then you were going to be ostracized as a writer. In fact, there are writers who experienced that.

I have always just tried to do my own thing and have tried to ignore it. And maybe even have tried to promote my writing outside of Canada, for that reason. But I think a lot of writers felt that writing what they really wanted to say would be risky.

TH: There’s a moment when your narrator provides his exact lineage, and notes that it corresponds precisely with that of the character he is writing about: 50% Ukrainian, 37.5% Irish, et cetera. This is a send-up of that trend, but it also seems to be a comment on what you’ve referred to as “the anti-literary focus on the person of the author,” something you’ve written about in the past. How do you see that trend impacting the Canadian cultural scene?

PS: I questioned my assessment of how prevalent that mode of thinking is — is it really as bad as people say? — so, I wrote an item about this very extreme focus on identity. And when I was researching it, I went and looked at various publishers’ websites in Canada. Are the author bios really all that focused on this very minute idea of identity? If you look at it objectively, I don’t think most Canadian writers are all in on this. But that kind of a mode of being an author really gets highlighted in a lot of the mainstream places.

Where I think it’s impacting Canadian writing is that I don’t think we’re seeing a lot of progress in CanLit, as a form of literature — as opposed to writing being seen as a kind of a platform for a political notion. The writers who are my heroes, people like Robert Walser and Abe Kobo … Robert Walser said that the role of the author is self-effacement. Whereas now we see this strong idea that your writing has to be connected to who you are as a person. I think that’s really a step backward. And maybe it’s disrespectful of the readers.

TH: How so?

PS: Because I feel that it’s promoting the idea that the writing is so closely connected with the author, that it is the author — and there is really no room for interpretation, or having one’s own take. It’s just a platitude, but Andrei Tarkovsky wrote that “a book read by a thousand different readers is a thousand different books.” I feel strongly that we’re being told quite differently here in Canada, in many cases.

TH: I was moved by the passages in the book about self-censorship. Every writer I know talks about this, and how insidious it is, and how hard it is to entirely shrug off. To what extent have you grappled with that yourself in recent years?

PS: Well, for one thing, one wants to write a book which is going to be sellable — in other words, to have someone publish it. So, I felt that I’ve had to make modifications to my writing, so that it has more of an emphasis on the things that I don’t really care about in writing, such as character development and narrative tension. In this book, I play with that. Because on a superficial level, it’s a crime story. But if you’re looking for a neat conclusion to that investigation, you’re not going to find it.

Also, I think that there are certain taboo topics in writing in Canada. I’ve spoken with other writers who have told me that they won’t write too much about sex in their work. Because in Canada, they think they’re going to be told they can’t.

TH: Speaking of the publishing world, there is a moment in Naked Defiance where the copy editor interjects and says they are feeling traumatized. We have seen these kind of uproars in the publishing world. What do you make of these arguments from publishing staffers about emotional safety?

PS: I don’t know what to say, I honestly find it very strange. I’m willing to read all sorts of work and have my views of the world challenged. So, I would have to speak with these people to find out more. Even though I’ve read all sorts of books that have perspectives that I might disagree with, I don’t think I have ever felt my safety has been endangered. In fact, maybe I feel safer, because if I know that someone is expressing a viewpoint — even one I disagree with — then it means that others can be free to do the same. And we’ll have a fuller conversation about the way the world is.

TH: The poet Michael Lista was on the Lean Out podcast this week, talking about the state of CanLit. In Canada, we haven’t seen a lot of satirical novels about the identitarian movement, even though it has been the water that we have all been swimming in for a couple of years now. Why do you think that is?

PS: I don’t know, I think that a lot of writers have bought in to the way things are. And I don’t think that we have a huge tradition in Canada of strongly satirical writing. There’s a notion of, how would you say, an externalization society — like all of the problems are over there. Things that could be excellent content for satirical writing are kind of ignored in Canada. There is so much that we could talk about, that is going on in our society. Not always but often when writers are writing about heavy issues, they will choose a setting that is somewhere else in the world. I hope that my novel Naked Defiance is one of many to come that are a little bit harder-hitting in their satire.

I want to go back to the point about toxicity on the left. One point I think that the novel makes is that extremisms are pretty interchangeable. And as a person who is of the left — and actually is quite sympathetic to the performance artists here, who are promoting a Situationist view of the world — I think the thing that harms our cause most is these kind of internecine politics, where people are trying to take down one another to see who is the purest. I think it’s very dangerous and it should be satirized. And I hope we’ll find other writers taking up this topic.

Not sure what you mean, Jowzer. Satirizing identity politics IS cutting edge territory. It’s felt dangerous for writers here to do it because they might have been shamed online. Likely less true now. Samplr is wrong, though, when he says Canadian literature doesn’t do much satire. There is a rich tradition of satire and irony starting with Mordecai Richler, Margaret Atwood, David McFadden and many, many others. The Canadian critic Linda Hutcheon says Canadian writers use 11 different kinds of irony in their stories. Samplr would benefit from getting acquainted with Hutcheon’s literary criticism and the satirical fiction of these other writers.

So glad that Tara is featuring “writers that are pushing back on the status quo”, especially that “skewer the extremist politics of our age.” Ordered the book, but out of stock for now . . .

With craziness being the order of the day, we do yearn for hopeful signs of sanity. Maybe, just maybe, literature might help. Glad that Literature is still a subject in our classrooms as stories do help people see different points of view. And good to see the 10th ed of The Moral of the Story, Introduction to Ethics (Rosenstand) is out and hope it’s being used in our colleges and universities. Downloaded Linda Hutcheon’s 11 pg Functions of Irony as recommended by Susan, thanks. I just finished a great book, VICTIM, by Andrew Boryga, which deconstructs the victim game to gain fame and a college degree. (It all crashes when fabrication is revealed!)

Now, my bit. Do we all know that Vancouver is legendary for having produced the best-selling book, The Peter Principle, a satire? Laurence J Peter (d 1990) was a School Board employee for 24 years and observed the principles of incompetence in hierarchies on the spot. A delightful short video from the BBC shows Peter in the early stage of his discovery (1974). Why, there are even PP Board Games designed by Peter. I remember in the 70’s attending Vancouver (Excelsior City) School Board meetings as a young parent when the trustees would sometimes joke around policies and personnel matters, using terms such as “lateral arabesques” and Peter Principle!

I do support the use of literature as an additional, important tool to help us grapple with the confounding and threatening events we are experiencing today. Hope this kind of literature — ridicule, satire, irony, comedy, etc. — becomes a flood that reaches the average person on the street where even PC (politically correct) narrative is still tricky.