In recent years, the conversation about race has been dominated by a certain kind of thinking, a version of anti-racism that stifles dialogue rather than opening it up.

This ideology — which New York Times columnist John McWhorter describes as “third-wave anti-racism” and author Irshad Manji calls “dishonest diversity”— is personified by scholars like Ibram Kendi and corporate trainers like Robin DiAngelo. It deemphasizes connection and common ground and a collective aim of improving concrete material conditions. Instead, it advances a rigid and irredeemable oppressed-oppressor binary, an inaccessible lexicon of buzzwords, and institutional policies and programs that discourage genuine discussion. It often portrays entire races as monoliths, erasing economic class, and geography, and education, and religion, and politics, and personality, and all of the other elements that make up our uniquely individual experiences of the world.

At its worst, this school of thought is long on dogma and short on humanity.

All of which is why it was such a relief this week to pick up a wonderful new book, Letters in Black and White. I learned about it from Lean Out guest Eli Steele, whose film, How Jack Became Black, had a profound impact on my own thinking about race.

In a lengthy Twitter thread this week, Steele praises Letters in Black and White as a “fresh departure from our racialized era of fear and self-censorship,” and says that “reading these letters moves one from the simplicity of racial essentialism to the complexity of our greater humanity.”

Letters in Black and White started with a diversity training, of all things. Several years ago, Jennifer Richmond — a China expert who’s worked in international relations for two decades — attended a publicly-offered seminar in Austin, Texas. She had recently founded a project encouraging people to communicate across ideological, racial, and gender divides through sharing letters. “I presumed this training was my chance to have these conversations in real time and face to face, in a setting explicitly designed for such a purpose,” she writes in Aero magazine. “I was wrong.”

“Diversity and creating unity through diversity was never a topic,” Richmond notes.

Instead, the workshop focused on white identity, ranking participants according to white privilege scores and dividing them into affinity groups. According to Richmond, “the training was crafted in such a way as to prevent authentic dialogue among racial groups, and disagreement was met with denial.”

Her essay on all of this, “Diversity Drop-Out,” was published in April of 2019, and it included a call for readers to contact her with their own thoughts and experiences. Winkfield Twyman Jr., an author and former law professor — and a staunchly independent thinker — took her up on it.

In his first missive to Richmond, he reflects:

Whenever I come across a highly touted “conversation about race” in the media, it always seems to be a conversation among the same handful of people echoing the same boilerplate script written for a public audience. All the while, these individuals act as though they are speaking for whatever race they happen to belong to and corrupt the English language for their own specific agenda. Such an approach might be good for their book sales or consulting fees, but when it comes to conversations that might actually create a meaningful difference that improves the Black Experience in America — and that might actually unite rather than divide — private grassroots conversations between individuals will bear the most fruit.

Later on in the letter, Twyman notes:

… let’s not forget, there is no one “Black Experience.” There are over 40 million black Americans. That means there are over 40 million different perspectives, life stories, and personalities. Painting with a broad brush strays from truth, a truth that is always nuanced and complex, which I’m sure you can appreciate. A person wouldn’t know this if they relied only on today’s diversity-training programs for their “education.” Such programs are so often wrong and offensive precisely because they put people like me — and you — in a box. The differences found within any given extended family are greater than any average difference found between races, however the term is defined.

What follows is a rich correspondence between two thoughtful, empathetic, engaging and extremely well-read writers trying to work through the difficult and disturbing history of race in America. We learn about Richmond and Twyman’s own family histories; Twyman’s family tree includes slaves, and both Twyman and Richmond count slaveholders among their ancestors. We learn, too, about the pair’s personal lives, their intellectual influences, and their ever-evolving views.

Letters in Black and White proves a tremendously satisfying read, in large part because the authors eschew orthodoxies. When one lapses into platitudes or party lines, the other pushes them to think more critically, to delve deeper. Together, Richmond and Twyman strive continuously for greater complexity, greater specificity.

Significantly, they resolutely avoid jargon. “To the greatest extent possible,” they write in the book’s introduction, “we both avoid words and phrases drained of real meaning, such as white privilege, white fragility, oppression, anti-racism, systemic racism, institutional racism, white supremacy, ally and woke. These words are clumsy, slippery, and manipulated beyond recognition. These words have themselves become caricatures. They mask real life in Middle America. We choose instead to use our brains and describe real moments drawing on the other three hundred thousand words in the English language.”

In the process of this correspondence, alternately challenging and encouraging one another, Richmond and Twyman exchange countless small courtesies and kindnesses. An understanding grows up between them, and, with it, a sense of trust.

In other words, they become friends.

“The best way to change our mindset is through connection — such as through the connection we are making here, in our correspondence,” Richmond tells Twyman at one point. “This type of connection is the antithesis of segregation. When we connect, when we interact and share our stories and our lives and take the precious time to do so, we change our hearts. We can see ourselves in each other, despite the myriad differences and distinctions that make us unique individuals.”

Reading these letters is restorative, regenerative. It is a lesson in humanity and hope.

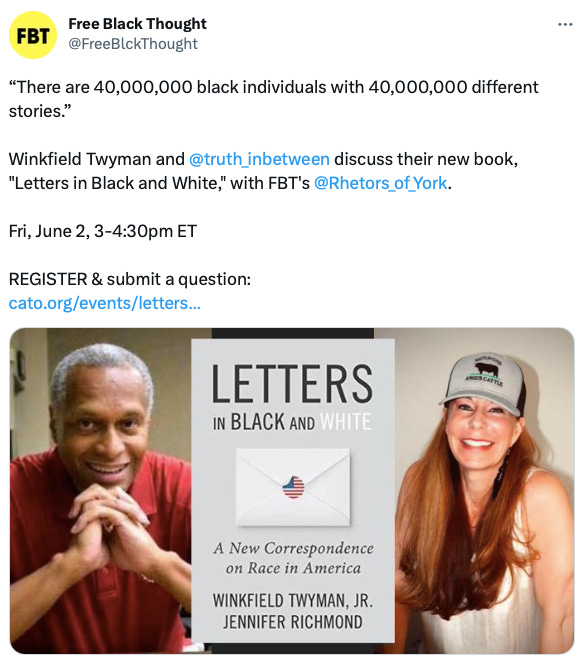

If you’re interested in hearing more, Richmond and Twyman are doing an event this Friday, with Free Black Thought’s Erec Smith, another thinker I admire, who penned the forward to Letters in Black and White. You can register for it here.

Moving on to weekly Lean Out updates, Lean Out guest Hakeem Oluseyi will be giving the commencement address for the MIT School of Science’s advanced degree ceremony next week. We send our congratulations! Also, Michael Powell at the New York Times recently revisited Oluseyi’s story on the paper’s podcast, The Daily.

Lean Out guest Kevin Bardosh has a new paper out on pandemic health measures, “How Did the COVID Pandemic Response Harm Society? A Global Evaluation and State of Knowledge Review.”

And if you missed it this week, my guest on the Lean Out podcast was UBC professor Azim Shariff, discussing a new pre-print paper on politicization and trust. I received a lot of reader mail on this one. One Lean Out reader wrote me to flag this blog post from the outgoing director and CEO of the Canada Council for the Arts, and this article on Canadian museums. Both good examples, to my mind, of the kind of politicization that Shariff and I discussed on this episode.

Stay tuned, the great Michael Lind, author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages is Destroying America, joins me on the podcast next week. See you then!

What would Scott Adams do?

Follow the Dilbert Rule.