With summer winding down and the Lean Out podcast about to go on hiatus for several weeks, I wanted to leave you all with a really compelling story — a story of one of Canada’s most famous journalists, an investigative reporter and war correspondent who cared deeply about the truth.

This is also the story of that reporter’s son and his quest to understand his father, a quest that took him around the world and inspired him to put pen to paper.

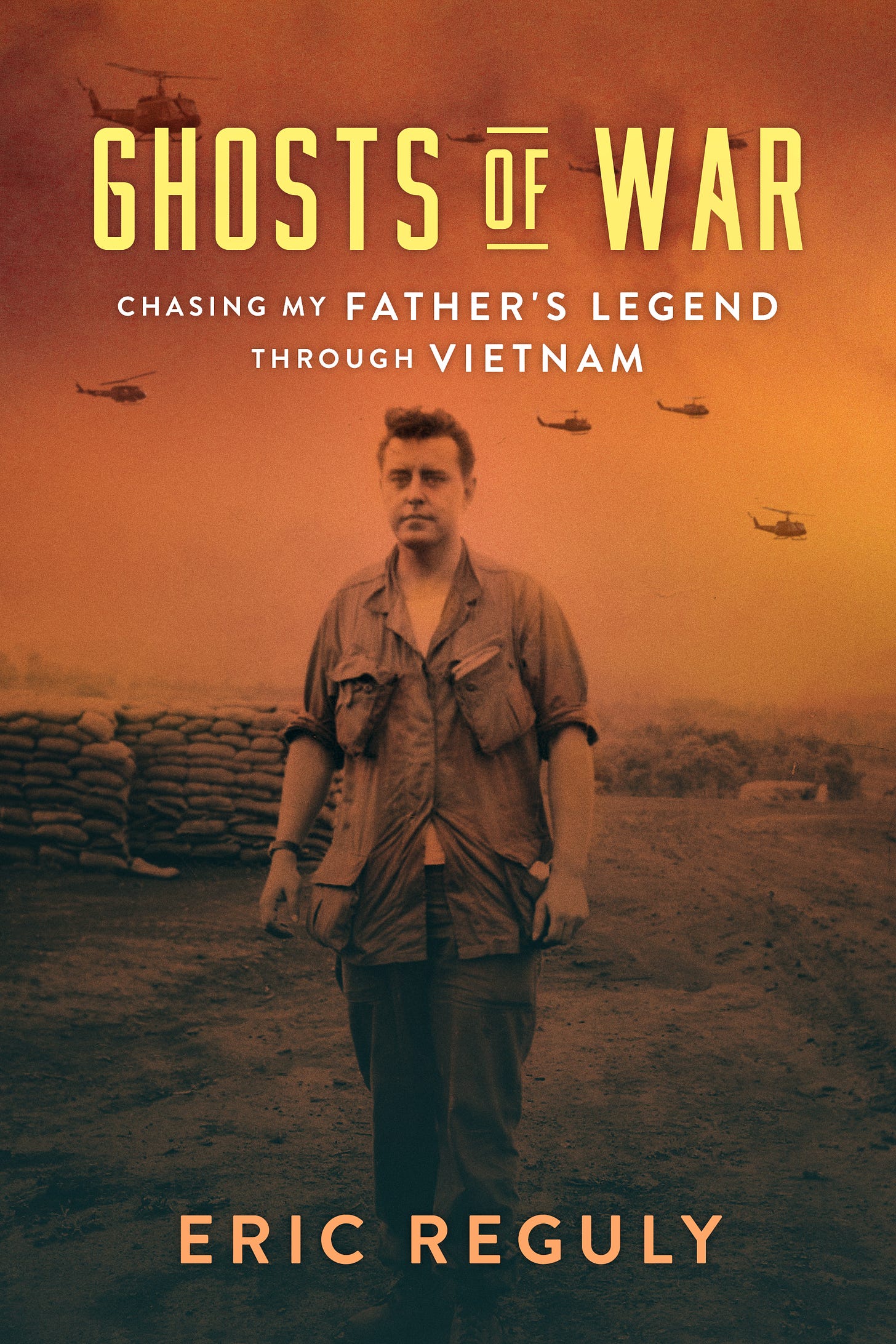

Eric Reguly is the European bureau chief for The Globe and Mail newspaper. He’s also the son of the late Bob Reguly. Eric’s new book is Ghosts of War: Chasing My Father’s Legend Through Vietnam.

I’m pleased to have Eric Reguly as my guest, for the last summer episode of Lean Out. An edited transcript is below.

Thanks, everyone, for the well wishes on my vacation — and for your wonderful support. See you in September!

TH: Eric, welcome to Lean Out.

ER: Thank you for having me, Tara. Pleasure to be on your program.

TH: So nice to have you. I found your book incredibly moving. I also learned a lot — about the Vietnam era, about the history of journalism. And about your father, Bob Reguly, a famous reporter whose legacy should not be forgotten. Let’s talk about his story, to start. What do listeners need to know about his early life to help them understand how he became the journalist that he did?

ER: He’s of Slovak descent. His parents, my grandparents, were born in Czechoslovakia, now Slovakia, very close to the Polish border. And they came to Canada around the turn of the century, about 1900. They went to where Slovaks went in Canada, Fort William/Port Arthur, which is now Thunder Bay, at the top of Lake Superior. They made lives there. They were not war refugees, but they were certainly poor. They came knowing no English. My father was born in 1931, right after the Depression started. And he had, by all accounts, Tara, a miserable upbringing. They grew up in a small farm outside of Fort William. I visited the farm and it was on the side of a mountain. I don’t know how they farmed it. Then they moved into the town, but they really had no money.

My father’s mother was treated as a slave. She had seven children to raise, including a couple of adopted children. My father’s tragedy was when he was five years old, a kid shot by accident — shot an arrow into his eye. It blinded him in one eye. But that wasn’t the problem. The problem was a scab grew over that eye and made him look like a freak. This white film that grew over his eye. There was no OHIP [Ontario Health Insurance Plan] back then. His parents didn’t know enough even to take him to the hospital, though he could have been cured.

Anyway, he felt like a freak. He retreated into books, and he discovered the world through books. I think that’s what gave Bob Reguly, my father, this yearning to see the world, to have adventures. He was very smart, incredibly well read. He was the first Reguly that I know of that went to university. He went to the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. He wanted to see the world. And, you know, it’s probably because he had this freak accident when he was a kid.

TH: He did see the world. He had an incredible career. He got big investigative scoops. Some of the biggest in The Toronto Star’s history, including tracking down the mobster Hal Banks. He covered racism in the States, the Civil Rights movement, the anti-war movement. He was in the room when Robert Kennedy was assassinated. He went to Gaza and Palestinian refugee camps. He went to Nigeria. He lived in and reported from many countries. But it was Vietnam that captured him — that, in many ways, defined him. Why do you think that conflict loomed so large for your father?

ER: It was, first of all, shortly after we moved [to the U.S.]. I was just barely old enough to remember what was happening. We moved to Chevy Chase. His reward for the Gerda Munsinger scoop, Canada’s first sex spy scandal, was being sent to Chevy Chase, Maryland to be the Washington, DC bureau chief for The Toronto Star. Back then, The Toronto Star was the show in Canada. It was Ernest Hemingway’s paper. It was the razzle-dazzle newsmaker. The Telegraph and The Globe and Mail were considered lesser papers back then. And the big story was Vietnam.

In 1966, the Americans thought this war would be over within six months. The Americans had won in World War II; they did not lose in Korea. And, you know, how could they not beat a nation of what they called peasant rice farmers? It’s a pejorative term, but that’s what they thought of them as.

And it was the big story, Tara — a huge story. And my father went there, as all good journalists do, he wanted to cover the big story. But it was also his first war. So it was a mixture of curiosity and also just being a good journalist. He wanted to go where the headlines are being made. He went in the late spring of ‘67. Again, the Americans still thought they’d win the war. But the war was just starting to go against them. My father went there and that’s what he wrote about. He said — which was considered heresy back then — that the Americans might not win this war. And he was right.

TH: Very striking. We will come to the climate that we’re in right now with journalism later, but I thought it was amazing that he took that stance. This book was a long time in the making. Take me back to the spring of 1998 when you met the legendary English photojournalist, Tim Page, who blurbed your book. When you realized that you needed to retrace your father's footsteps in Vietnam.

ER: Tim Page. Wow. You know, I’m going to Australia [this month] to see Tim. He is a chapter of my book. Tim Page is no doubt the most famous surviving combat photographer of the Vietnam war. He lives in Australia. He was born in England. He’s a wild man. He was doped to the gills. They would ride motorcycles into battle during the Vietnam war. He defined the liberty and freedom of the era. There were no restrictions for journalists in the war in Vietnam. They could go where they wanted, when they wanted. The concept of embedding — which is what happened in the Iraq war — did not exist then. I met him when he was releasing his book Requiem, which is a marvel. It’s a collection of the photographs of all the photojournalists who died in Vietnam, on both sides of the war, men and women.

It’s a haunting book. It brought tears to my eyes, this book. I interviewed him and I was absolutely captivated by him. We had a couple of hours together at the end of the book launch event, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where I used to live. I said, “Did you meet my father in Vietnam?” He said, “No, I don’t remember him.” My father didn’t remember Tim Page either. Though, of course, they knew of each other. But they don’t remember running into each other. [Tim] said, “What we did back then was extraordinary. And we probably helped bring this war to an end.” Because this war was broadcast to the living rooms of Americans, for the first time in history. To the living rooms of tens of millions of Americans, hundreds of millions. And they were horrified by what was happening in the war.

He’s the one who convinced me. He said, “Eric, you have to go to Vietnam and retrace your father’s footsteps.” That’s what gave me the idea. But my mistake was, Tara, I hesitated. I hesitated for 20 years. Life took over, kids took over, I moved to the Rome bureau of The Globe and Mail. And I didn’t get there until 2018, which was then seven years after my father died. Which was a tragedy for me because some spots I could not find where he went. And also, I just missed not being able to talk to him about what he saw, where he saw it.

TH: Yeah. You were able to be guided by his Toronto Star stories; a note that he wrote you before he died helped as well, it sounds like. You looked at his movements in 1967. This became a 9,000-word story in The Globe and Mail. That became the seed of this book. The reporting from that trip is hugely evocative. And I have seen video of you in Vietnam, close to where your father was in a foxhole at one point. Very emotional. Give us one or two snapshots that really stand out from that time.

ER: Two come to mind. Now, I tried to retrace the steps as closely as possible, using his original copy from The Toronto Star. I had a few photographs, not many, interviews with a few people he worked with in Vietnam, and notes he gave me shortly before he died. So it was like putting a puzzle together. Almost immediately after he arrived in Vietnam in early June of 1967, he went to where the action was. He went to the demilitarized zone, which is the strip of land that divided North and South Vietnam.

He went in with 700 Marines in this horrific Con Thien battle — one of the most horrific battles of the war. There were 500 casualties. At one point, a Marine handed him a shovel, a gun, two grenades, and a bag of marijuana, and said, “We don’t protect war tourists.” Meaning journalists. “You’re on your own.” He had to fight his way out. He almost died. He fired his gun several times at night. He says he doesn’t know if he hit anyone. But he said the North Vietnamese would come running across the foxhole field at night. And he thought he was going to die for sure. So he fired his gun. I said, “Dad, did you kill anyone?” He said, “Yeah, probably, but I don’t know for sure.” I said, “Dad, you’re a journalist, you’re not supposed to do that.” He said, “What would you have done in my case?”

In fact, there are many cases, Tara, of combat photographers and reporters who had to fight their way out of battles that went against them. Some of them didn’t make it. I sort of got that.

But anyway, I tried to find the spot on the Ben Hai river where he was in this foxhole. I think I got close. I found the bend in the river that he talked about. I was probably, I don’t know, several hundred meters from the foxhole. But I didn’t feel his spirit there. Vietnam has changed. It felt like a subdivision. There was a karaoke bar across on the north side of the Ben Hai river that was blasting this awful music. I wasn’t allowed to walk around because this was the most bombed part of the world in history. Every year, thousands of Vietnamese either get killed or wounded from an ordinance that was dropped by the Americans. So you’re not allowed to wander around in the forest, or even by the river because there’s unexploded landmines, bombs, grenades, everything. That’s the one spot I wanted to feel his presence, but I didn’t.

But I did feel his presence about a week later. We went to the Vietnam side of the Cambodian border, where the Montagnards lived, and still live. My father wrote this really riveting, compelling story, including photographs, of a forced evacuation of an allegedly communist Viet Cong village. They, at gunpoint, forced them all onto these big twin rotor helicopters. And they flew them out. Anyone who refused to get on the plane, on these helicopters, was considered Viet Cong or a Viet Cong sympathizer, and was shot. So it was a forced evacuation. This happened a lot in resettlement in the whole area.

We went into this tiny village. They grow cashew nuts there. But it was a restricted area and I did not have a permit. Neither did my fixer, nor our driver. The driver was very nervous, and said, “Look, we have got to get outta here.” I said, “I need 15 minutes.” I asked my fixer to ask anyone to bring out the oldest men and women in the village — and fast, as soon as you can can. I met this one old man in his 80s. He was slouched, moving slowly. We went into his house, a very simple house. Underneath his bed, he had a helmet. An American helmet that that was used for storage. So I knew he was aware of the war. I gave him a copy of the newspaper that showed the Montagnards being evacuated from this area in June 1967. Through my fixer, I said, “Do you remember this?” He said, “Yes, I was there.” He wasn’t speaking very well. I think he had chemical damage, maybe from agent orange. We’re not sure.

But he was a sweet old man. And he looked to me like a ghost. He went back in time, 50 years, 51 years, to that moment when he was evacuated.

I felt at that moment, Tara, that he saw my father then. And that my father saw him. He may have been, as a young man, even in the pictures my father took. I know this sounds odd, but that moment just pierced me. It haunted me. I felt my father’s presence. I was in the exact spot where he was in 1967, talking to the same people he talked to. Initially I felt hollow, and then I felt this tingling of excitement because I actually — I felt my father’s presence. I wrote this in the book. I felt closer to my father at that moment than at any time since he died. It was a wonderful, wonderful moment. I was just tingling.

TH: It’s a really strong passage in the book. What a moment. I want to talk, for a minute, too, about the conditions that your father was working under in Vietnam. As you point out in the book, reporters enjoyed a kind of freedom of access, and freedom of movement, that is now unheard of. Even in your father’s time, though, there were those who stayed at the hotel and re-wrote the military press releases. But I found it really striking, as you said earlier, that he came home, anti-war and anti-U.S. foreign policy, something he did not refrain from talking about. Talk to me about what you see as the benefits — if we can even say that, because I know it was horrific enduring some of those experiences — but talk to me a little bit about what you see as the benefits of that style of reporting that he undertook.

ER: That’s a good question, Tara. The benefits of unrestrained reporting, I think, are huge. As I mentioned before, my father went over to Vietnam in mid ‘67, right at the height of the war. Just before the Tet Offensive in early 1968. The war was still considered highly winnable. My father discovered the opposite and was brave enough to report that. Now, if he had been in embedded as the war correspondents were in Iraq, I doubt he would have come to the same conclusion. In fact, I have talked to Iraq war reporters and some of them — even though the body count was astonishingly high in that war — didn’t see a single body. Because they weren’t allowed to see a single body.

Because they were embedded, the Americans and the British, who were with them, only took them … basically showed them propaganda areas. Where there were no dead children, no dead women, no blown-up schools. On the other hand, the Vietnam war correspondents saw everything. The only restriction they had was not to report the precise locations of American soldiers in battle, in a fire fight, because then the North Vietnamese could find out exactly where they were. But other than that, there were no restrictions.

What was the benefit? I think the benefit was that the American audience — remember, this was the first TV war, but newspapers back then were very strong — that Americans got the truth of this war fairly early. The anti-war riots and mass demonstrations started in ‘67 and they just exploded in 1968.

Remember that Lyndon Baines Johnson, who was the President then, was expected to run for reelection in 1968. And he didn’t. He just called it quits. This was evidence that he had lost the war on the home front. How did that happen? Because of honest and truthful and accurate — savagely accurate — journalism, that was allowed to come out of Vietnam. Because there were none of these restrictions. The Americans learned from this experience. Because in subsequent wars, there was huge censorship. And in Iraq, you had to be embedded or you couldn’t get anywhere near the war.

TH: You also wrote about how your father filed his stories, which I found fascinating. You referenced this in a recent Globe piece about those covering Ukraine. Talk to me about how he got his stories back to Toronto.

ER: Oh, God. Every journalist who covered the Vietnam war said the hardest part was getting the stories out. First of all, and this is obvious anyone who is older than 40, there was no Internet back then. There were no iPhones. It was almost impossible to make a landline call out of Vietnam. My mother only knew my father was alive — she had a terrible time when he was in Vietnam — when she saw his byline in the paper, in The Toronto Star. But then she realized that the story that she was reading, say Saturday in The Toronto Star, was probably written Thursday. So was he alive two days later, or a day later? She had no idea. And the foreign desk in Toronto had no idea either.

When he was in a fire fight, he would have to take a combat helicopter back to a combat base. If there was no teletype machine there, he would have to take another helicopter to a military base big enough — a logistical base that had a teletype machine — or even fly all the way back to Ho Chi Minh City, then Saigon, to file. This was really, really dangerous. Because you had to leave a fire fight in a battle. You had to get on a truck or helicopter to a military base and another military base. And there was danger along all the way. I don’t know this for sure, but my father said that a few journalists, perhaps many, got wounded or killed just trying to get their stories out. It would take a day or two to get the stories out. And, you know, photographs were a whole other issue. It took even longer to get photographs out.

Today, it takes me 10 seconds to file the story, no matter where I am. I press send on my computer. That was not the case back then. So I was in awe of the danger they took. The patience they had, the creativity. My father said that he would walk around with a stack of $20 U.S. bills to bribe the Vietnamese who had access to teletype machines. To get in front of the queue. Or else they would have to wait for days to get their stories out.

TH: Just a wild, wild time. You write that your father basically would do anything for a story — and your mother and your family did suffer for that, ultimately. But it also instilled in you the desire to be a reporter. Your father’s legacy, at one point, became a bit fraught, because of the way his career ended. Let’s just spend a moment on that part of his story and the impact that had. What was the last story that he covered, that ended his career?

ER: Oh, God. This really shattered the family. We’re still seeing the effects of it. My father went from being Canada’s most famous print journalist to being a zero, and it virtually happened overnight. He teamed up with another journalist, Donald Ramsay, to write a story about insider trading of Petro-Canada’s purchase of a Belgian oil company called Petrofina. Back then, Petro-Canada was a crown corporation. They accused a cabinet minister, John Munro, of using insider information to buy shares of Petrofina before the Petro-Canada purchase — and getting rich off this advanced knowledge. This information came from the second reporter on the story.

By the way, I should mention the only time my father had a double byline story was this one. He was a loner. He trusted no one but himself. The one time of his life that he trusted this young journalist, now dead, it turns out that this journalist Ramsay did not have the insider trading records that he claimed to have. My father was devastated. My father had to resign on the spot, which he did. It ended his career. Why had he trusted this man? I don't know. My mother doesn’t know. We ask ourselves this, to this day. It was heartbreaking. He lost his job the day I graduated from journalism school, at the University of Western Ontario in 1982, I think it was.

TH: Wow.

ER: Yeah. There I was, getting my master’s degree in journalism, having studied my own father’s fame in journalism school. My father came that day and he was completely shattered because he had just lost his job. He never recovered. He got abandoned by his friends. There was financial distress that came in into the family. My mother, having raised three children — who was unhealthy even then — had to go to work to make ends meet. It really destroyed us. It haunts us to this very day.

Because we cannot answer the question. Even though he was a cynical, hard-ass truth warrior journalist, he also had this oddly trusting side about him, where he was very trusting of friends or people he considered friends. And unusually generous with them. He had a really good heart that way. He trusted this Ramsay. You know, I met Ramsay once and my instincts went right up. I thought, “No, this is a wild man.” I didn’t quite understand the story then, but I remember thinking, “I hope my father is doing the right thing by trusting this guy.” It was exactly the wrong thing. It destroyed his life and his health.

TH: This book is not just a personal story. It is also the story of our profession — and how much our profession has changed. In some ways, for the better. As you point out, your father’s era was a very macho one. The trauma from the carnage he saw rarely came out. Whereas for you, covering the aftermath of 911 in New York City, there was a little more room to express that grief. You and I both worked throughout the pandemic and it really underscored the changes journalism has gone through. In my 20 years, we’ve gone from being out all the time, to then doing mostly phone journalism, to now being on Zoom. You write this is not good for our profession. In what ways do you think our profession is suffering for this detachment we now have?

ER: I definitely think it is suffering. Back then, to learn about an event, a story, you had to pick up the phone and talk to someone. That era is gone. Yes, I make a special effort to talk to people. But sometimes, many times, for me and other journalists, it’s, “Email me a quote.”

But something else has changed, Tara. Back then, the public relations industry existed, but it didn’t exist in the many layers and sophistication that it does now. I think this has damaged reporting to its core. Even in my early days in the mid 80s, when I first started my career, before the Internet, you could still pick up a phone and talk to a Member of Parliament, even a cabinet minister, even CEOs once in a while. You could get an interview without having to go through six layers of PR.

In Europe, they want to know, when you ask for an interview with someone — there is not quite the freedom of press as there still is in North America — they want a list of your questions even before the interview. They want to review the questions before they even grant the interview. And when stray off from the emailed questions, they get really upset. That’s happened to me many times in Europe, in Italy, where I live. Certainly in the Middle East. Certainly in North Africa. It’s very hard to get around the handlers, the PR men and women, the spin doctors, that control access. Access is much harder to get now. I think that’s damaging the industry.

TH: Absolutely. Another thing that occurs to me is that in your father’s lifetime, journalism went from being a working-class profession … your father’s ethos really seemed to embody that to me — this kind of plain-talking, truth-telling, rabble rousing culture … to now being an elite profession. Your father lived by that saying that we’re supposed to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. How do you think our profession is doing with that these days?

ER: That’s another good question. I think that newspapers and television channels, Internet news services, they tend to be lazy and they tend to hire from journalism schools. First of all, you have to have minimum BA, probably an MA, and you almost certainly have to have been at a journalism school. I never believed — and don’t believe today — that the best journalists come out of journalism schools.

What are the qualities of a good journalist? It’s aggression, not taking no for an answer, savvy, street smart, endless curiosity, endless energy. Those are the qualities, that make a good journalist. And, you know, as you said, to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. We’re not getting that as much as we used to. I think that in some cases, the wrong journalists are being hired.

Why did I go to journalism school? I learned nothing in journalism school. Really. I went because I knew that I probably could not get a job unless I went to journalism school. Because The Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, The Ottawa Citizen, all these papers would just take journalism school interns, and take the ones they liked. It shouldn’t be that way. I don’t think journalism can be taught. I think it’s largely instinctive.

We think journalism is competitive now. It was horrendously competitive back [in my father’s era], because newspapers were big and rich, and they lived and died off of scoops. You know, the Gerda Munsinger scoop was basically a fatal blow to The Toronto Telegram. It just put the Star on the map and every other newspaper paled in comparison. Yes, my father went to university, but he didn’t go to journalism school. He just had those qualities — skepticism, energy, cynicism — that made a good journalist.

TH: Having been through this process of writing the book, going on that trip, spending that time in the pandemic reflecting on all of this, how do you feel about your father now?

ER: I have always loved my father. Even though he never told me that he loved me; he just couldn’t express emotion that way. When I was a kid, Tara, I always considered my father a thrill-seeker. Here’s a guy who worked his way through university jumping out of airplanes with parachutes into forest fires in Northern Saskatchewan. I mean, this is not a normal job. This is not working at McDonald’s flipping hamburgers for minimum wage. This is a guy who always lived on the edge, always doing dangerous things. I thought maybe he went to Vietnam — and that was one of four wars he covered — because he was simply a thrill-seeker.

What I learned in this book was that, no, he was an accidental war correspondent. That he was primarily an investigative journalist, who, by happenstance, having lived in Washington in the late 60s, was sent to cover the biggest story of the era, which is the Vietnam war. He was not a natural war correspondent. He had never been a war correspondent in the first 20 years of his career. It just landed on his lap.

This book helped me reevaluate what kind of man my father was. What kind of reporter he was. And I realized that, yes, he was unusually brave. But I don’t think he was motivated by seeking thrills. I think he was motivated by seeking the truth. I know that sounds corny. What journalist wouldn’t say that? But he was absolutely devoted to getting the other side of the story, to getting the truth. Even if it meant risking his life. I learned from research in this book that he didn’t go to Vietnam because he needed that cocaine high. He did it because he wanted to find out what was happening.

He came back dead-set against the war. He was in a minority then, saying the war was going to be lost. He was telling our neighbours and friends in Chevy Chase this war was done. And he was ostracized. No one would talk to him after that, because that was considered sacrilege. But he was brave enough to learn this, and to write this.

I think what I learned about my father was that he was not just motivated by excitement, the daily adrenaline rush. That he really was a truth warrior. And my respect for him has soared. I love him more than ever now.

Share this post