There’s a lot of things that we don’t talk about in our society right now. And one of those things is fatherhood. The role of fathers — and the power of their presence, and care — is not explored that often, or in much detail. But my guest on the podcast today says that needs to change.

Shaka Senghor is one of my favourite writers. He’s a tech executive, a New York Times bestselling author, a former fellow at the MIT Media Lab, and a leading voice on criminal justice reform. Formerly incarcerated, he served 19 years in prison, seven of which were in solitary confinement.

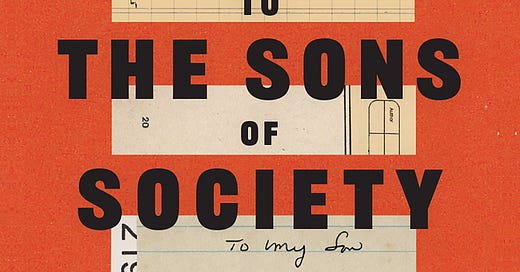

Shaka’s powerful new book is called Letters to the Sons of Society: A Father’s Invitation to Love, Honesty, and Freedom — and it is written to his two sons, and to all the children in our world at large. Shaka Senghor is my guest, today on Lean Out.

TH: Shaka, welcome to Lean Out.

SS: Thank you so much for having me. I’m really excited to catch up. It’s been a while since we’ve talked last.

TH: It has been. Last time we sat down, we were in your kitchen in Koreatown in the Before Times.

SS: Yeah, that was a while ago. I’ve actually moved since then, and bought a home here in L.A. So, no longer in that apartment with the glorious view. But happy with the home that we have.

TH: It’s great to be able to talk today about your new book, which is exquisitely written. I want to open with reading a passage:

I have told the world about the murder. I have told the world about the life I led that brought me to that terrible point. I have told the world about the forgiveness for which I begged and that I was fortunate to receive. I have told the world about my hopes for other incarcerated children and men and women, my dreams of a new way of looking at how we rehabilitate instead of punishing … But I have never told the world, nor you, my dear sons, about the nights when the luggage looms in the darkness. The nights that I am forced to breathe, really breathe, take a step away from yet another ledge and remake myself once again before the dawn arrives.

What a powerful passage.

SS: Thank you so much for reading that and reflecting it back. It definitely just transported me back to those moments. You know, oftentimes when we’re doing work that speaks to our personal stories, people aren’t thinking about the toll, or the impact, that it has on us as individuals. And I really wanted to capture that for my sons. So they’ll understand what it’s like to have your personal experiences, especially those less-than-stellar moments, on public display. I wanted to ensure that they understood what that looks like when it comes to solving tough problems, and giving people a path forward.

TH: And turning those moments of darkness into this incredibly beautiful writing, and this experience of humanity.

SS: For me as a writer, it is really respecting the craft. When I think about my first book, I think people got so immersed in the story that they didn’t account for the fact that I’m actually a writer. I have studied the craft. I’ve read some of the most beautiful, and incredible, writers that we all know of. For me, anytime that I think about the stories that are important for me to tell, and that I feel led to tell, I also think about the creative process. How do you tell these stories in a way that’s really inspiring, uplifting, and insightful?

TH: I do want to talk about this book in depth, but before we get to that, for listeners who may be new to you, new to your work — can you give us a snapshot of your backstory? How you went from being a young honour roll student growing up on the east side of Detroit, dreaming of being a doctor, and then going to prison and finally coming out and becoming this New York Times bestselling author.

SS: That’s a great question. At this stage of my life, I don’t talk much about that part of my journey. I think because I’ve written so extensively about it. However, I do think it’s important to contextualize these conversations. As a kid with dreams of being a doctor, and with all the possibility and potential in the world, unfortunately I grew up in a very difficult household that I ran away from. I thought that I would be welcomed into somebody else’s home and wrapped in the love and care that all children are deserving of. But unfortunately I found myself seduced into the drug trade, where I encountered high levels of gun-related trauma, including being shot at the age of 17. And then 16 months later, tragically shooting and causing a man’s death, and repeating that cycle of PTSD and gun trauma in my community.

I was sentenced to 17 to 40 years in prison, and ended up serving a total of 19, with seven of those years being in solitary confinement. And it was in solitary confinement when my journey as a writer and a storyteller and a truth-teller really began.

Fortunately, after 19 years, I was released back into society, in June of 2010. So I’m actually coming up on my 12th year of freedom. I have done a tremendous amount of work around criminal justice, around personal transformation, and efforts to end gun violence in the inner city. As much as I do other stuff in the world, I’ll always be passionate about working with young men and women who come from communities and experiences similar to mine.

TH: This book is interesting because you’re talking about fatherhood and masculinity. It is inspired by letters your father wrote to you when you were in prison. In fact, his letters are on the cover of the book. Talk to me about what those letters did for you.

SS: For the 19 years of my incarceration, my dad wrote me. He would write these beautiful, handwritten, long letters that really encapsulated the world he was navigating being the parent figure for my oldest son, Jay, who he was taking care of due to my incarceration.

One of the things that was great about the letters between my dad and I were the life lessons about being a man, being a father, being a husband. But also his sense of humour, his insights. We were able to share things we were reading, our perspective on what we read. We were able to agree; we were able to disagree. Most importantly, we were able to heal some of the broken pieces of our past. To unpack life choices that I made that led me on the path that I was on, but also life choices that he made.

It’s just an incredible gift from a dad to a son. My goal with this book was to not only give that gift to my two sons, but to the sons of society at large. And those who love the sons: The dads, the moms, the sisters, the lovers. I think this book really speaks to the humanity in all of us, even though it’s directed toward my two sons.

TH: I want to talk about your two sons. The first letter to Jay is so powerful. Talk about your process writing that — it’s a very vulnerable, very raw letter.

SS: That first letter was probably one of the harder letters to write, because of the depth of emotional vulnerability and the honesty. The things that I got wrong as a dad, the things I came to understand about myself. Then there’s just the horrific realities of inner city life, and thinking about what happens to Black boys. And thinking that my son was a victim of circumstances that so many young men in our community have been victimized by, which is the high levels of gun violence. Oftentimes, as parents, we find ourselves taking our children on journeys that they didn’t agree to.

When I got out of prison, I had this idea of who I thought I was as a father, and who I thought I needed to be. And it couldn’t have been further from the truth.

A lot of dads, we try to mentor, we try to coach. Sometimes our children really just need us to be present. I missed a mark on that. I really wanted to share that with my son, so that he would understand. But I also mentor so many young children across the country, and even outside of America. I find that that pattern is similar when it comes to dads. We show up as the heroes, the disciplinarians, the ones who are like, “Here, let me straighten you up, so that you’ll be ready for the world.” Really, what children need more than anything from their dads is just our presence, and the confidence that that gives children, and the freedom that it gives them to navigate life.

TH: In the book, you expand the narrative around fathers, and the way that we see fathers, and think about fathers. I want to read another quote.

There is a trope in our culture of the absent father and the sainted single mother, but the reality for so many of us is actually agony. Do you really think we want to be away from our children? Who would choose such a thing?

We have learned to take the second road, to acquiesce to the image of us as less than, as inadequate to the task of love. We are not inadequate to it. We yearn for it, but so often we find ourselves out here in the garage of our lives, away from the main rooms, steeling ourselves for either loss or reentry.

SS: Every time I think about that passage, I get really emotional. Because I have incredible friends in my life who are amazing dads. I come from a family where all the men are really present. They’re not just present as providers, they’re nurturers.

I think about when I was 16 years old, and I attempted to commit suicide. It was my dad that sat by my bedside, and nurtured me, and helped me get back to a healthy space. I’ll never forget him sitting on my bed and rubbing my head. Even though he didn’t have all the answers, he had his presence. That emotional availability is something that I’ve seen historically in my family.

Even now I can go home and I have an uncle, his name is Chris. He will still fix me a plate. I’m a grown man. I’m 50 years old. But it’s just that care that I’ve witnessed with my friends and the men in my life. That narrative never gets talked about.

My dad cooked, my dad cleaned the home. My dad also worked and provided, and did all the other things that are typically associated with manhood. But none of the things he did were one-offs; they weren’t outliers in our family. Me as a dad, I’m relatively successful, but there’s still things that are important for me to do. It’s been that way since Sekou was born. I’ve always been a caretaker of him; I’ve always been a nurturer.

There’s moments where Sekou is like, “Dad, I want a hug.” I’m fully present in that. There were some things that I didn’t experience in my childhood that my dad and I, we talked about. Because he hadn’t had those experiences.

But as I got older, and I was going through the most difficult time in my life, my dad showed up as the most incredible nurturer you can imagine. He was the one who was there on those visits. He was there to hug me, and love on me, and make sure I was able to eat some food outside of the prison food. The narrative around dads — those things need to be included. And they don't have to be included in a way that takes away from what mothers have historically done. But we also don’t need to be beat down because we decide to share what brings us joy in parenting.

TH: We’re in a funny moment for talking about masculinity. On the one hand, there's the progressive dialogue about “toxic masculinity.” I understand that. We talked last time in our interview about the kind of masculinity you saw in prison and how limiting that is. So I understand that. But in some ways, “toxic masculinity” can limit talking about what it means to be a man and a father as well. Do you find that?

SS: Absolutely. I think the terminology is like a lot of terminologies now in our pop culture. A lot of those things have lost their original flavour and their original intentions. Now they’re weaponized in a way to dismiss behaviours that we either don’t understand, or we’re uncomfortable with.

I think it is hypocritical, honestly. Because on the one hand, we’re talking about, “How do we create this collective culture of centering our humanity?” But then on the other hand, there’s this othering when we are using language that doesn’t really contextualize certain behaviours. I think it’s a lazy approach. It’s where we’re at as a culture — we don’t lean into intellectual dialogue. We’re not curious enough to really understand why people behave in the manner they behave in.

The easiest thing is to dismiss their behaviour, with language that erects a wall as opposed to builds a bridge. I try to steer away from that language. What I try to do is lead with my humanity, which is an ever-evolving thing.

As long as you’re living, you’re evolving, you’re growing. There’s potential to bring in new information; there’s potential to learn new things. I think that is really important when we’re talking about, “What does it mean to be masculine?” Sometimes there’s contradictions that may seem counterintuitive. Can you be a nurturer and still love football on Sundays? Can you be anti-interpersonal violence, but tune in to the latest boxing or UFC match?

To me, that’s the complexities of being a man. I don’t think we talk enough about how complex the emotional makeup of men really is. We’ve simplified us to these barbaric tropes, and it couldn’t be further from the truth.

TH: I wanted to talk about cancel culture, something I’ve written about a lot. You’re actually the first person that I learned about cancel culture from, in our last interview. Walk me through your feelings about where we’re at with cancel culture.

SS: I think we’re at a real sad time. Again, I think it points to intellectual laziness. I don’t think that we actually care about solving the thing. I think we’re more interested in exalting ourselves at the expense of somebody else’s misstep, misdeed, or poor judgement.

Because of how I live my life, my personal story, I believe in redemption. I believe that people should be given an opportunity to atone. I think people should be given an opportunity to make things right. That requires an invitation from us all. Exiling people, because they have an opinion that’s not popular, without understanding how they arrived at that conclusion — that does a disservice to us as human beings. It doesn’t allow us to grow. It doesn’t allow people an opportunity to heal. To reinvent themselves, or reimagine themselves.

TH: I want to switch gears for a moment and talk about racism. You’ve written to your sons about the fear that you feel at certain points as a Black man in America. There’s a moment that stands out in the book when you are cleaning dog poo in the middle of the night. Tell us that story.

SS: We had just got a puppy, who unfortunately is now deceased. We had got this beautiful puppy and like many puppies that are growing, they get sick. They eat something and they have a bad reaction. Our puppy was being crate trained. He was really little and he pooped all in the crate, and it was just the most horrific smell at three in the morning. I hadn’t been in my home long, maybe seven or eight months in a new neighbourhood. I’m one of the only youngish Black men that I see on my block. I dress in a way that’s more aligned with hip-hop culture, which is where I come from.

I remember bringing the crate out. It was a noisy affair. I’m dragging this big old crate out of the house. I’ve got to wash the crate down. I remember freezing in panic. It’s L.A., but L.A. nights are really chilly. I’m in black jogging pants, a black hoodie, and I’m out here in this new neighbourhood making all this noise. What I was thinking is: What if one of my neighbours called the police? And: When the police arrive, what does that encounter look like? It was terrifying to think that it’s three in the morning, I don’t have my ID on me.

In that moment, it was paralyzing. I had to do some self-talk. Like, “Okay, this isn't happening. This is just a thought that’s triggered by all these other things that do happen. But this is not what’s happening right in this moment. Clean the poop up, get the puppy in to safety, you’ll be fine.” But that’s what it’s like being Black in America, Black in a society that has demonized Black men specifically.

Our stories often are not told fully … I was just talking to my girlfriend last night and we were talking about the levels of gun violence, and the death rate for Black males in America. The reality is if as many white boys were killed in America by gun violence as Black boys are killed, it would be considered a humanitarian crisis. And we don't treat it that way. So, the perception is that Black male life has little value in society. That’s one of the things that I really want to change.

TH: You also wrote about a moment outside a barbershop and how that moment was able to shift. Can you tell us that story?

SS: I was in Cincinnati and somebody had made a false call and said that a group of Black guys were obstructing traffic. Actually we weren’t even in the street; we were on a sidewalk in front of a barbershop that had just won a grant. The police were called and a young white police officer came and we ended up having an exchange that turned out to be very powerful and very beautiful, because we both leaned into our humanity.

When I asked him what was going on, he told me about the false call. I told him that he should come into the barbershop and meet the owners. He was hesitant to do so because he felt like his uniform alone would cause the party to go flat.

I told him Jerome Bettis, Hall of Fame, NFL football player, was inside. Initially he didn’t believe me. So I went and got Jerome Bettis and he came out. The officer got really emotional because Jerome Bettis was his dad’s favourite player and his dad had passed. In that moment, we were just three boys. It wasn’t Jerome Bettis, the NFL football player. It wasn’t an officer; it wasn’t a writer. It was just three boys, talking about our dads and our experiences as men.

I ended up writing a Facebook post and it went viral. That really spoke to me about where we’re at. I think people are wanting more hopeful outcomes. I think people are wanting to see more of these stories — that actually happen all the time.

There’s the system. And then there’s the people. We have some systems that are bad that good people exist in. I really wanted to highlight what it looks like when you lean in to your humanity.

TH: Such a great story. To close, Shaka, you mentor young men. What do you think society is not seeing about these kids? What do you want everyone to know?

SS: What I want everyone to know is that boys crave love and acceptance in a way that we haven’t really thought about. They crave emotional intimacy … Every time I’ve mentored a group of young boys, it starts off with that hard shell. But once that shell is peeled back, you see these beautiful children who are trying to understand the world and their place in it.

We don’t allow our boys to be kids long enough. We’re too busy trying to usher them into adulthood, into manhood. We’re missing out on letting them navigate their innocence for as long as possible, and joy that comes with that. Because with innocence comes curiosity, and with curiosity comes great adventures. I think we have to create space for our boys to go on more great adventures, and to be as curious as anyone else in the world. And to be affirmed with love and affection.

That creates healthier adults. It creates more loving men, more caring and compassionate men. But we can’t expect men to grow up and be compassionate, loving, and vulnerable, if we shut that down while they’re boys. If we tell them to stop crying, if we tell them to toughen up when they’re actually hurt. If we tell them to run away from love because that makes them weak. Then we create weak men.

What I would say is love your boys in a way that you would desire to be loved, so that they can grow up to become loving men. If we can expand the narrative around that, I think it’s a game changer.

TH: That’s a lovely place to leave it. This is such a powerful book. It is so well written. I hope everyone reads it. Thank you for coming on today.

SS: Thank you so much for having me, and looking forward to more.

This transcript has been edited and condensed.

Share this post