The pandemic, as we know, has been a different experience for different people. Some of us, the laptop class, isolated and worked from home. But others of us, the essential workers, were out there every day doing the work that it took to keep society from collapsing.

The stories of the working class have often gone untold, but my guest on the podcast today has dedicated himself to interviewing working people — on his podcast, in his reporting, and in his new book. And he believes their experiences deserve to be heard, and remembered, and thought about.

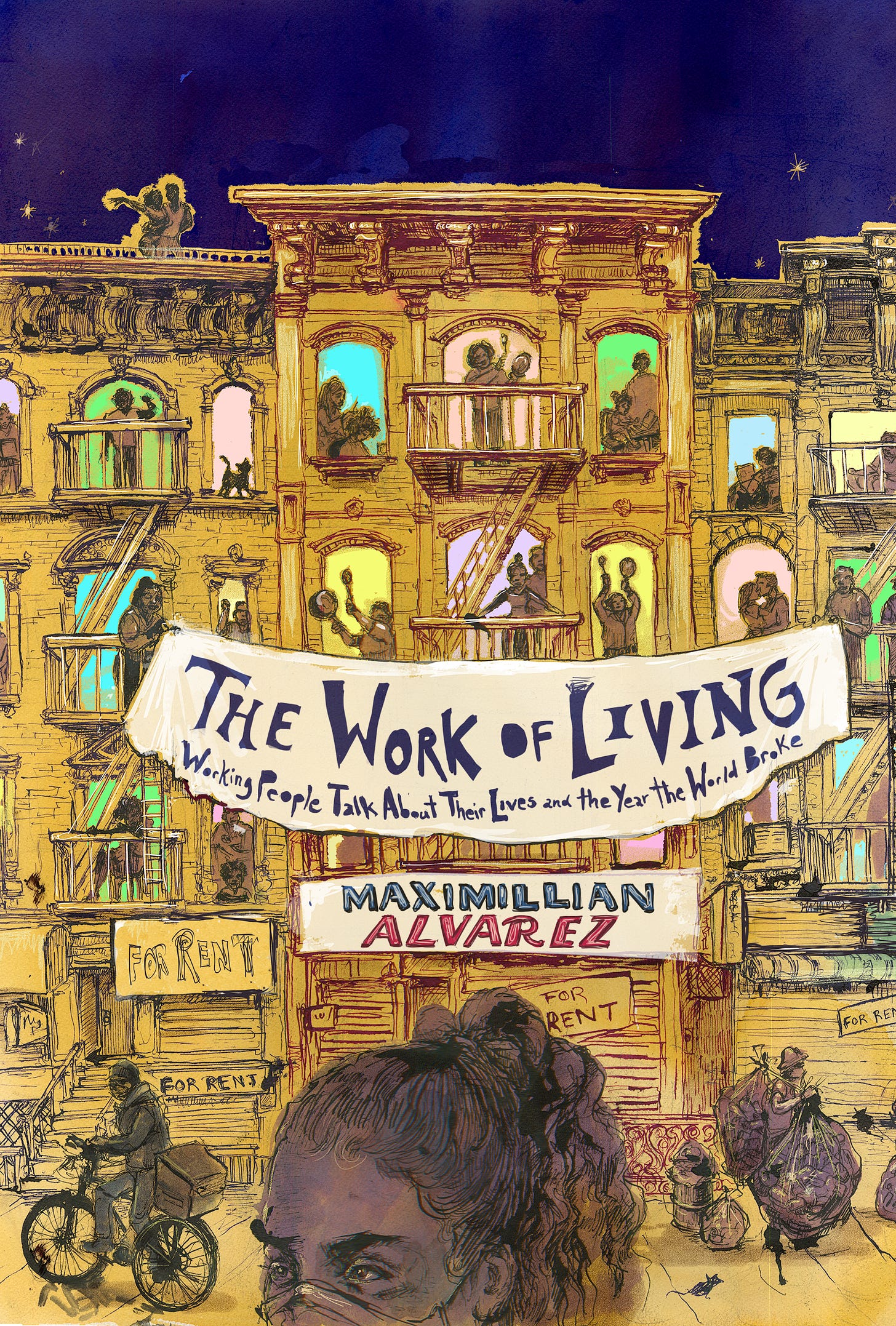

Maximillian Alvarez is a writer and editor based in Baltimore. He’s the host of the Working People podcast, a show about the lives of the working class. He’s also the editor-in-chief of the Real News network, and covers labor for Breaking Points with Krystal Ball and Saagar Enjeti. Maximillian Alvarez’s new book is called The Work of Living: Working People Talk About Their Lives and the Year the World Broke.

Below is an excerpt of the transcript. For the full interview, download the podcast.

TH: Maximillian, welcome to Lean Out.

MA: Thank you so much for having me.

TH: I’m really excited to speak with you. We will get into the book in depth. But first, I want to spend some time on you and your story. I want to start by reading a quote from another book that I know has inspired a lot of your work, and that is the oral history Working from the great Studs Terkel, which you quote in your powerful monologue kicking off your own podcast. Studs Terkel writes, “It is a search for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash.” Talk to me about how Studs Terkel has informed your work.

MA: Big shout-out to the legend Studs. Like you said, I quote from his book Working in the introduction to the very first episode of Working People, which was an interview with my dad, Jesus Alvarez. I think that a lot of my own story, and the origins of how I came to do this work, can be found in that episode.

I was born in Orange County, Southern California, first generation Mexican- American. Growing up with my siblings, it was always a big part of our upbringing to hear the stories from both sides of our family. The stories of struggle, the stories of working their way up from poverty — both sides of the family have long histories of poverty.

My dad was born in a shack in Tijuana. As we talk about in that first episode, his mother got sick and passed away from cancer when he was just six years old. Their father had abandoned them; he was a migrant farm worker in the United States and he just stopped coming back and stopped sending money over. So, they were really on their own at that point. It was my great-grandma who promised my dad’s mom on her deathbed that she would bring her children to the United States. My great-grandmother had connections with immigrant churches in Southern California. It was through those churches that she managed to find families in different parts of Southern California to adopt my dad and his siblings. So, they were split up.

I’m very thankful for the podcasts that I do, because it gave me an opportunity to get those treasured family stories — that I’ve been hearing all my life — on a recording. Right now, we have a number of sick family members, some of whom I may never get to speak to again. And I’m racked with guilt and regret that I didn’t get the chance to record with them. So it’s made me all the more appreciative of those recordings.

There was even one that we did that was a follow-up to the one that I did with my dad, where I got the rest of his siblings and a bunch of our family members on. It was incredible. There was a moment where my tios were talking about losing their mom and being split up, and at some point everyone at the table just started crying. My dad said on the drive home that day, “That’s the first time all of us have sat down and talked about our mother dying.” I’m glad that we were able to take advantage of that moment and that it could provide some healing.

Then, on my mom’s side, my grandpa Fletcher was born at the end of the Great Depression. He was one of 13 siblings in North Carolina; he had his first job when he was six. So, we always heard those stories growing up as kids. We always internalized it. Like, “That’s what our family went through for us to get here.”

I was fortunate to be born into a middle-class home that my folks had bought and raised a family in for a brief time. And then, when the Great Recession hit, it all went away. But for the first 18 years of my life, we grew up in our home in Orange County. The world still seemed open to us, and the future seemed open to us. We focused on school. We were always told that it was our job to carry on [the family] struggle by getting a good education, by not getting into crime and gang activity.

I grew up very conservative and my dad, in fact, when he became a citizen — the first person he ever voted for was Ronald Reagan. On that first Working People episode, we talked about how he voted for Donald Trump in 2016. He explained that we lost everything during the Obama administration. We were constantly being told about an economic recovery that seemed to be passing us by. And so he felt desperate. He knew all the problems with Trump, but he was hoping that maybe a miracle could happen and we would get some help. And of course that didn’t happen.

The importance of family storytelling has always been there for me. But I noticed that after the recession, we weren’t telling those stories as much. We weren’t talking to each other nearly as much about what we were going through. We were instead just doing what good capitalist subjects do, which was punishing ourselves for being colossal failures.

It was destroying our family in a lot of ways. My parents’ marriage was on the rocks. Our relationship with our parents was on the rocks. I had graduated college in 2009, so I got spat out right into the recession. I basically had two useless Russian literature degrees. Obviously I find a lot of value in them, but at that moment in time, there wasn’t really much that I could do with them. I had moved back home thinking that I was going to help out while I was figuring out my next move. Instead, I ended up working temp jobs, showing up at the temp agency at four in the morning to get whatever job I could — just so that we could have money for groceries and gas.

That was a big radicalizing period for me. It was when a lot of that conservative upbringing and ideology started to fall off like cracked paint. I was looking at our family and myself. I was like, “I did everything I was told to do. I still ended up working 12-hour days as a temp in a warehouse.”

First, I was like, “What did I do wrong?” But then I started talking to coworkers. I started seeing what my family was going through. They didn’t do anything wrong; they’ve been working their butts off. It felt like something bigger was wrong here.

That was a really important experience for me — working alongside a bunch of formerly incarcerated folks and undocumented guys. You get into conversations about what’s going on in each other’s lives. You learn more about each other. You lean on each other. You build these great bonds. You really learn to see each other as human beings, and you build that solidarity that can be very lifesaving in moments like those.

In the years after that, that’s when we finally lost the house. Of course my parents were very depressed about that. They stopped going to our church. They didn’t talk a whole lot to friends and family. I could see with my dad especially, it was like the lights were on but no one was home. Somewhere inside of him, he was punishing himself so deeply for all that he had had and lost.

My mom was doing the same too, but she was at least she was a little more communicative with us. But it was really ripping us apart. In a lot of ways, the podcast was almost a ruse to get my dad to talk about the trauma that we had gone through … He suddenly opened up in a way that he hadn’t in years.

I think a big part of that was because he had been driving Uber and Lyft, just to pay the bills. He wanted to keep his ratings up, so he would get into conversations with the people he was driving. It was then that he realized that he was driving people who were his age, who were also immigrants, who had lost their homes, who were on their way to their second or third job. He started to realize that it wasn’t just him. That there were other good people who had lost everything, because an unjust system had screwed them over.

I think that was very important for me to witness, because it made me realize, once again, that power Studs Terkel articulates in his book Working. The world-changing power of working people sharing their stories with one another, and believing that their stories — our stories — are worth sharing. I really try to honour that tradition with the podcast, with the work I do at the Real News, and with this new book.

Share this post