Weekend reads: Censorious Times

Attending a film, buying a book, or seeing a comedy show? Better watch your back.

We are now at the height of summer — a time when, not too long ago, people in the media used to slow down and unplug. In Canada, CBC Radio would air a constant loop of pleasantly banal reruns, the Toronto headquarters eerily empty, with all of its hosts and a decent amount of its producers having escaped to cottages in the woods, armed with stacks of books that had been languishing on nightstands all year, and prepared to ignore breaking news developments (not that there were many). Similarly, in the big media centres in the States, the press corps, like all other elites, beat a hasty retreat, abandoning the sweltering streets and hightailing it to sleepy rural hamlets with, one would imagine, delightfully unreliable WiFi.

Now, of course, there is no such pause. No reprieve. No break in the relentless news cycle. The outrage fest marches on uninterrupted, and this past week, that meant story after story of alarming censoriousness.

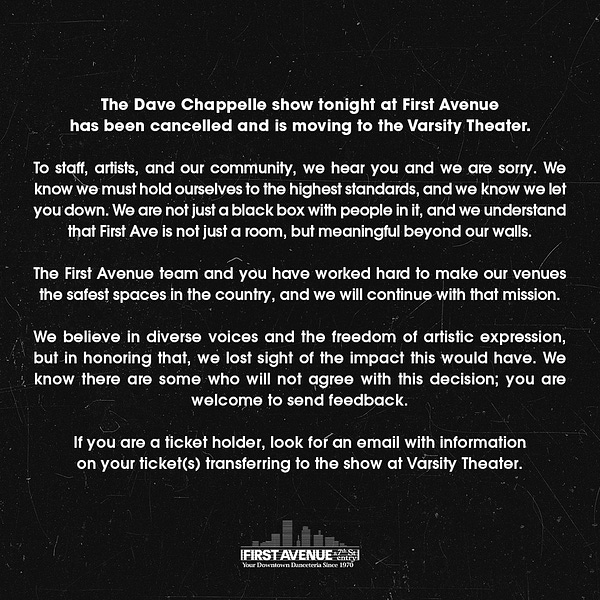

Ten days ago, Dave Chappelle had a show cancelled at the iconic First Avenue in Minneapolis, which, in a different lifetime, did not have its lineup dictated by social media scolds.

Now First Avenue is home to boilerplate hostage apologies.

Quick question: Who goes to a comedy show to feel “safe”?

This week we also saw a shameful hit piece on author Thomas Chatterton Williams, accusing him, of all things, of attending a film premier.

The Gawker story claimed that Chatterton Williams went to the Austin premier of Alex Moyer’s new documentary about Alex Jones — which proved false.

The idea that attending a documentary about a controversial public figure is some sort of moral transgression is the absurd endpoint for the guilt-by-association fallacy, which I have written about in the past.

I reject it. So much so that I’ll probably download the movie just to make a point.

Here’s an important reminder from Matt Taibbi:

In the pre-Trump era it was understood reporters weren’t supposed to avoid ugly or scary topics. We were supposed to dive right in, and in the nonjudgmental manner of doctors figure them out. That was the job, but somewhere along the line it became taboo to ask the usual why? questions about the likes of Trump or 4Chan surfers or the subject of Moyer’s new movie Alex’s War, the infamous InfoWars host Alex Jones.

The difference between understanding the world or not can depend on whether your journalists of choice really inquire about difficult topics, or whether they’re the believers in the media equivalent of Lamarckian evolution, thinking rage, discontent, and populist uprisings appear out of nowhere, like flies spontaneously generating on carrion. Not long ago, no one outside the Bush White House (and certainly no journalists) believed “Bad people are just bad,” but now we have versions of those truisms to explain almost every species of malcontent, especially Trumpian conservatives, 4Chan trolls and other reasonless pestilences. Journalists now aren’t supposed to look too closely at their motivations, and most don’t, wearing incuriosity like a badge of honor.

The Gawker TCW piece is part of a pattern in the mainstream press, which is mainly okay with an appalling erosion of journalist standards — if it involves “problematic” people. So, in this case: No calling the subject for comment; no swift and total retraction when a piece is proven to be fabricated; no embarrassment over having gotten it wrong.

Gawker published a hit piece on me a while back, which also trafficked blatantly false claims, all of which could have been easily debunked had anyone bothered to check the facts. But then, the point wasn’t the facts, was it?

Moving on to Canada, land of excessive politeness (except when we’re freezing protestor’s bank accounts), it recently came out that the bookseller Indigo has declined to stock a bestselling book — Andrew Lawton’s new outing on the trucker crisis, The Freedom Convoy: The Inside Story of Three Weeks that Shook the World. It is available online, but the company has said there isn’t space for it on the shelves.

Jen Gerson at The Line has a good piece on this. (You can also read an excerpt of The Freedom Convoy here, also at The Line.)

It’s hard to imagine how a corporate bookstore justifies not selling a popular book — particularly the first one on the biggest news story in our country’s recent history — but it makes sense if you believe that books exist not for reading, or even buying, but as elaborate signalling devices.

As Gerson points out:

In fact, Indigo has decided to go the way of virtually every other cultural establishment in this regard, including media outlets. It has curated not only its product, but its customer base, serving an ever-narrower audience the product that aligns with its values and self perceptions. Thus ensuring that we shop, socialize, and inform ourselves in ever smaller bubbles of mutual amity, defining ourselves by our shared and common enmities.

Let’s turn our attention, now, to the world of book publishing, which is, by many accounts, a hot mess. (Sensitivity readers, covered in this Lean Out podcast interview with Kat Rosenfield, being one of the many forms of censoriousness currently plaguing the industry.)

Pamela Paul has published a solid opinion piece in The New York Times, “There’s More Than One Way to Ban a Book.” I include this salient quote here:

We shouldn’t capitulate to any repressive forces, no matter where they emanate from on the political spectrum. Parents, schools and readers should demand access to all kinds of books, whether they personally approve of the content or not. For those on the illiberal left to conduct their own campaigns of censorship while bemoaning the book-burning impulses of the right is to violate the core tenets of liberalism. We’re better than this.

To close: To any and all journalists uninterested in, or actively hostile to, free speech: If you can’t support it on principle, or for the health of our democracy, do it for self-interest.

You do realize that without a free press, we don’t have jobs, right?

Censoriousness was also a focus on the Lean Out podcast this week, in a discussion with professors Amna Khalid and Jeff Snyder on their recent essay on cancel culture. Transcript coming tomorrow for paid subscribers.

The confusing part of all of this, and I think it points to why most of us never worried it would get this bad, is attributed to the belief that the artistic entertainment elite would never allow it.

It seems that because their monetizing fame game changed to accumulating followers and likes on social media (and preventing Twitter mob attacks) instead of just delivering art we would pay for, they jumped to virtue signaling support for their fan base demographic.

But it is a sell-out... a conflict of their artistic freedom capability.

It starts on campus, but it permeates society. I think if the artistic elite wake up to reject this crap, then the kids might too. But so many are brainwashed, it might take a generation to repair.

Good stuff except, perhaps, the bit by Pamela Paul. The New York Times has proven over and over that they cannot be trusted.